|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

The Soviet lunar effort was officially begun in 1964 when Premier Nikita Khrushchev gave the full go-ahead to proceed. A manned lunar mission required the development of both technology and procedures to safely travel to, land on, and explore the Moon. The Soviets had successfully mastered many of these criteria, including spacewalks as well as rendezvousing and docking with other craft in space. By the end of 1966, 18 cosmonauts were in training for lunar missions, including Yuri Gagarin who had been the first man to orbit the Earth. Furthermore, the Soviets had developed and built their own lunar lander, known as the LK, that was tested in Earth orbit during the Kosmos 379, 398, and 434 missions of 1970 and 1971.

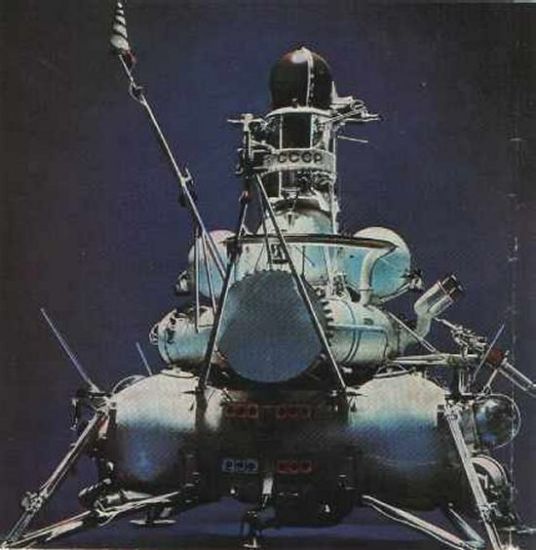

The Soviets had also developed their own equivalent of the Apollo Command Module called the LOK. Known as the lunar orbiter, the LOK was a derivative of the Soyuz capsule modified to carry a crew of two to and from the Moon. Though a complete LOK never flew in space, many of its features were tested on Zond missions that will be discussed in a future article.

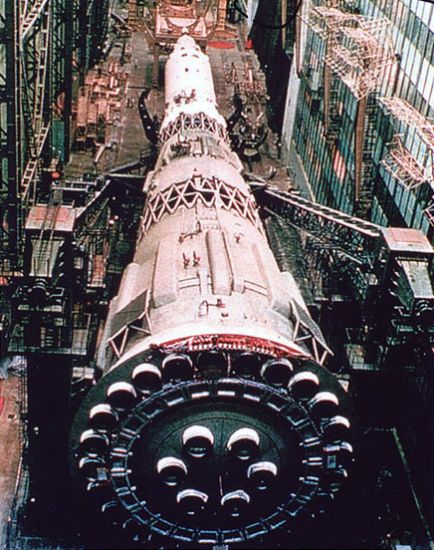

The one major hurdle left before a cosmonaut could land on the Moon was to develop a rocket powerful enough to make the journey possible. That rocket was the N1, also known as the SL-15 or G-class booster in the West. Weighing in at 2,800 tons and standing 345 ft (105 m) tall, the N1 was equivalent to and roughly the same size as the American Saturn V.

The N1 was a rather complex system made up of a number of different stages and components. The first stage, known as Block A, stood 100 ft (30 m) tall and was designed to provide over 11 million pounds (50 million newtons) of thrust during the first two minutes of flight. Generating this thrust was a combination of 30 separate liquid rocket engines burning a mixture of liquid oxygen and kerosene. The second stage, Block B, was nearly 68 ft (20.5 m) in length and contained another 8 rocket engines generating over 3 million pounds (14 million newtons) of thrust for another two minutes. A third stage, Block V, used four more engines to provide the final push into orbit.

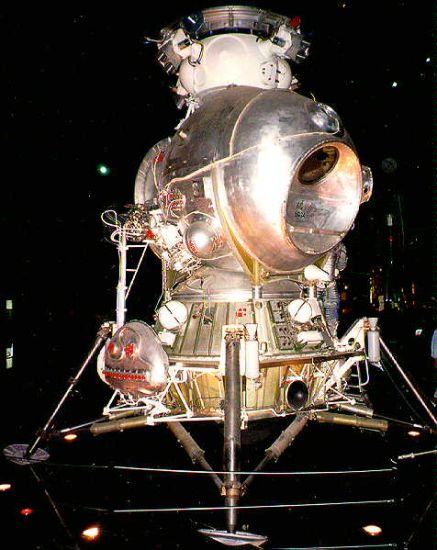

The remainder of the vehicle was collectively known as the L3 and contained all the components needed to travel from Earth orbit to a landing on the Moon. At its base were two more sets of rocket stages called Block G and Block D. Riding atop these stages were Block E, containing the LK lunar lander, and Block I, containing the LOK lunar orbiter. Additional information on these components of the N1 including cut-away drawings of their internal structures are available at Russian Space Web.

Despite its size, the payload carried by the N1 was only about 70% as large as that launched to the Moon by the Saturn V. While the Apollo missions carried a crew of three, two of whom would land on the lunar surface, the Soviets designed their craft for only two crewmen. The reduction in crew allowed the sizes of the LK lander and LOK orbiter to be significantly reduced, and one cosmonaut would remain aboard the orbiter while the second landed on the Moon. The L3 layout also had no tunnel directly connecting the two manned modules, so the second cosmonaut would have had to make a spacewalk to transfer in and out of the LK lander before and after his trip to the surface.

Though seemingly more complex, the Soviets believed this approach could be developed more quickly than Apollo and would allow them to beat the Americans by making the first lunar landing as early as September 1968. However, this plan turned out to be woefully optimistic. While some blame rests on the LK and LOK vehicles whose designs fell behind schedule, the ultimate failure of the Soviet manned lunar program rests squarely on the N1. At least nine examples of this enormous rocket were completed and four were launched on unmanned test flights. Unfortunately, all four failed in spectacular fashion.

The first vehicle launched was designated launch vehicle 3L. The rocket successfully lifted off the launch pad on 21 February 1968, but trouble struck almost immediately when a fire broke out in the Block A first stage. A safety system within the N1 reacted to the fire by mistakenly shutting down all 30 engines prematurely 68.7 seconds into the flight. The remainder of the doomed N1 then fell back to Earth in a catastrophic explosion. Just weeks later, the Apollo 9 mission succeeded in fully testing the American Lunar Module in Earth orbit, and the Soviets knew they had no hope of beating the Americans to the Moon.

The next N1 test flight came on 3 July 1969, only weeks before Apollo 11 made its successful lunar landing. Known as launch vehicle 5L, this N1 was also destroyed shortly after liftoff due to a failure in the first stage. Just 0.25 seconds into the flight, the pump of engine number 8 ingested debris and exploded setting off a large fire in Block A. The N1 managed to climb just above the top of the launch tower when the remaining engines were shut down prematurely. The rocket plummeted back onto the pad in a spectacular explosion that destroyed the launch facility known as 110 East. Not only did it take 18 months to repair the pad, but the failure ended any last remaining hope of impressing the world prior to the American lunar landing.

No further attempts to launch the N1 were made for nearly two years as engineers struggled to understand the rocket's flaws. Further complicating matters were constant political battles within the Soviet space program between those who wanted to kill the N1 project and abandon a lunar landing program and those who hoped to keep the effort alive. The project probably would have been cancelled had it not been for the near disaster that occurred on Apollo 13. Following an explosion aboard the Apollo service module en route to the Moon that nearly cost the lives of the three astronauts, the Soviets were convinced that NASA might cancel further Apollo missions. Such a decision might give the Soviets an opportunity to resurrect their own lunar landing program and regain the lead in the space race.

Given this reprieve, Soviet rocket engineers were allowed to test the much improved 6L vehicle on 26 June 1971. Upgrades to the design included fuel filters to prevent what had happened on the second launch as well as other reliability enhancements. Despite these improvements, the N1 faired little better than it had before. During ascent, the N1 developed a roll that its control system was unable to compensate for. As the rocket began to veer off course, the payload section started to disintegrate while passing through max q. Control of the N1 was completely lost 50.2 seconds after liftoff, and ground controllers were forced to activate the self-destruct system. Even though it was considered a failure, this flight did demonstrate significant improvements in the reliability of the first stage since all 30 engines functioned properly.

Nevertheless, June 1971 proved to be a disastrous month for the Soviet space program. Just four days after the N1 launch failure, cosmonauts Georgi Dobrovolsky, Viktor Patsayev, and Vladislav Volkov were killed while returning to Earth at the conclusion of their Soyuz 11 mission.

The subsequent investigations following these two tragedies resulted in a significant reorganization of the Soviet space program, and further N1 testing was delayed for over a year. Despite attempts to cancel the N1 program, one more unmanned test flight was approved. Vehicle 7L was closest to the final configuration needed for a lunar landing and also included control system modifications to avoid the roll problem observed on the previous flight. Liftoff occurred on 23 November 1972, and the rocket functioned as planned until 106.3 seconds into flight. Only seven seconds shy of first stage burnout, propellant lines in Block A ruptured causing engine number 4 to explode, and the vehicle began to disintegrate. The remains of the N1 tumbled out of control and crashed downrange from the launch pad.

This failure was the last nail in the coffin for both the N1 program and the entire Soviet lunar landing effort. After spending 17 years and 6 billion Rubles designing and developing the nation's first heavy-lift rocket, the N1 was officially cancelled in 1974 along with all lunar landing plans. All remaining N1 rockets were ordered destroyed, but some components still exist today at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan.

Getting back to your question, you ask whether the N1 crashed on the Moon shortly before the Apollo 11 landing. As we have seen, that is impossible since the N1 was never able to reach Earth orbit, let alone the Moon. I suspect you may be confusing the crash of the second N1 that occurred 17 days before the Apollo 11 landing with an unmanned Soviet probe that crashed on the lunar surface during the Apollo 11 mission. This probe was part of the Luna series of orbiters and landers launched by the Soviet Union to explore the Moon between 1959 and 1976.

Luna 15 began its journey on 13 July 1969 as a last-minute attempt to regain national pride in the face of the

pending Apollo landing. Luna 15 was a fairly sophisticated craft designed to land on the surface of the Moon and

collect soil samples to be launched back to Earth. It was hoped that the soil could be returned prior to Apollo

11's splashdown making the Soviets the first to bring lunar material back to Earth. Though the probe was

successfully launched and made its way into lunar orbit, bad luck again struck the Soviet lunar program. Luna 15

had completed 52 orbits of the Moon when it attempted to make a soft landing on the surface. Unfortunately, the

final retrorocket burn failed and the probe crashed in the Sea of Crises on 21 July 1969, just one day after Neil

Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin made their historic walk on the Moon.

- answer by Jeff Scott, 3 October 2004

Related Topics:

Read More Articles:

|

Aircraft | Design | Ask Us | Shop | Search |

|

|

| About Us | Contact Us | Copyright © 1997- | |||

|

|

|||