|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

However, another event that occurred in the Soviet Union in 1960 is generally recognized as the single greatest disaster in the history of rocketry. The event was not directly related to manned space flight, but to the development of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). In the early days of space flight, both the US and Soviet space programs were very much intertwined with the development of ICBMs. These vehicles were designed to launch nuclear warheads over great distances, leaving no part of the world safe from the threat of nuclear destruction. However, the technologies pioneered for these weapons of war served a secondary purpose of providing the first generation of rockets for space exploration.

In fact, the early flights of Sputnik and Yuri Gagarin in the USSR as well as those of Explorer I and John Glenn in the US were all conducted using modified ballistic missiles. The primary Soviet launch vehicle of the period was the R-7 rocket, modified versions of which are still used even today for most Russian space flights. The R-7 was originally developed as an ICBM under the direction of Sergei Korolev, the Soviet Union's pre-eminent rocket designer of the day. The R-7 successfully completed a number of test flights between 1957 and 1959, including launching the first two artificial satellites. While only four examples of the R-7 were ever deployed as ballistic missiles from 1960 to 1968, the same basic design has remained in use throughout the Russian space program. Modern variants of the R-7 continue to launch satellites as well as manned Soyuz flights, and the type had achieved a success rate of nearly 98% in over 1,600 launches by the year 2000.

However, a competing rocket designed by Korolev's former assistant Mikhail Yangel was also under development in the late 1950s. This new rocket, the R-16, was a more powerful ICBM intended to supersede the R-7. The R-7 had been deemed impractical for military use because it needed cryogenically cooled liquid oxygen as a propellant, which necessitated complex storage and fueling systems. The R-16 ICBM was instead designed to use fuels that were easier to store, giving the missile a much faster response time. Since the R-16 was considered a top priority by Soviet leadership, oversight of the project was given to Marshal of Artillery Mitrofan Nedelin, the commander of the Soviet Strategic Rocket Forces (or nuclear missile forces).

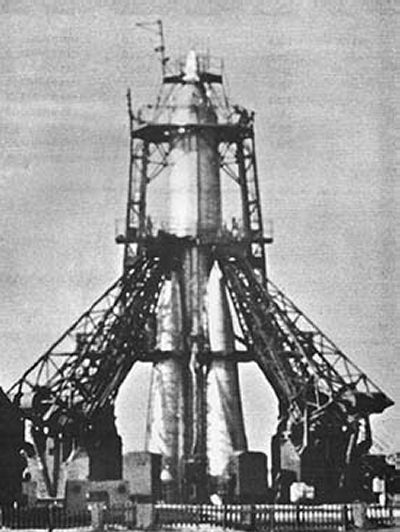

Under Marshal Nedelin's prodding, the design team worked furiously to complete the first R-16 rocket as soon as possible. Although the development was hampered by numerous unsolved technical problems, chief designer Yangel reluctantly agreed to deliver the first missile to the test range at what is now the Baikonur Cosmodrome in September 1960. Both Nedelin and Yangel hoped to please Premier Nikita Khrushchev by demonstrating a successful launch of the R-16 prior to November 7, the anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution.

Nevertheless, technical problem with the flight control system continued to plague the test preparations. Despite these obstacles, the rocket was moved from the assembly building to the launch pad at a location called Site 41 on October 21. At this point, fueling of the rocket with its toxic and highly corrosive propellants began. Proper safety protocols insisted that all non-essential personnel evacuate the area during fueling operations in case of an accident. However, Nedelin ignored these regulations and reportedly set up a chair at the pad from which he could oversee the arrangments. Approximately 150 other civilian and military personnel also stayed at the site under his direction.

As preparations for the launch continued, increasingly more fuel leaks and electrical problems began to emerge. On October 23, a number of electrical faults occurred that prevented the propellant pumps from working properly. The rocket would have to be drained of fuel before beginning repairs, but Marshal Nedelin refused to do so since it would delay the launch by at least several hours. He instead ordered workers to perform their repairs on the rocket while its dangerous propellants were still aboard.

Repairs continued to drag on the next day prompting Nedelin to demand to be taken to the pad "to figure out what's going on." In addition to Nedelin and his subordinates, Yangel and a number of visiting dignitaries were also taken to the pad to personally direct the pre-launch operations. The presence of so many powerful figures put great stress on the workers, and the situation was only made worse by pressure from Moscow to launch as soon as possible. Many tests and other operations were being conducted simultaneously, and safety procedures were neglected to save time.

The most significant oversight involved a device called the Programming Current Distributor (PTR) that activates various systems on the rocket. Following a test, the PTR was accidentally set to the wrong position. This mistake caused the batteries and propellant lines on the rocket to be activated, meaning that only a single valve prevented the rocket engines from being ignited prematurely. When a technician accidentally reset the PTR, that last safeguard was removed, and a horrible sequence of events was set into motion.

At about 6:45 PM, with some 250 personnel and visitors crowded around the launch pad, the second stage rocket engine of the R-16 ignited. The exhaust immediately ripped through the fuel tank in the first stage, creating a massive explosion that sprayed acidic chemicals across the launch complex. The luckiest were those who were instantly incinerated in the ensuing fireball that engulfed the rocket. Others died more slowly as they were burned while trying to escape through the raging inferno. Still more were able to evacuate the immediate vicinity only to be suffocated by the poisonous gases created by the burning propellants.

Massive explosions continued to rock the launch pad for about 20 seconds, and the subsequent fires lasted for two hours. The blast was reportedly visible as far as 30 miles (50 km) away. Below are quoted some descriptions of the disaster from witnesses to the dreadful events:

"At the moment of the explosion I was about 30 meters from the base of the rocket. A thick stream of fire unexpectedly burst forth, covering everyone around. Part of the military contingent and testers instinctively tried to flee from the danger zone, people ran to the side of the other pad, toward the bunker...but on this route was a strip of new-laid tar, which immediately melted. Many got stuck in the hot sticky mass and became victims of the fire...The most terrible fate befell those located on the upper levels of the gantry: the people were wrapped in fire and burst into flame like candles blazing in mid-air. The temperature at the center of the fire was about 3,000 degrees. Those who had run away tried while moving to tear off their burning clothing, their coats and overalls. Alas, many did not succeed in doing this."

"...automatic cameras had been triggered along with the engines, and they recorded the scene. The men on the scaffolding dashed about in the fire and smoke; many jumped off and vanished into the flames. One man momentarily escaped from the fire but got tangled up in the barbed wire surrounding the launch pad. The next moment he too was engulfed in flames."

"Above the pad erupted a column of fire. In a daze we watched the flames burst forth again and again until all was silent...(After the fires had been extinguished,) all the bodies were in unique poses, all were without clothes or hair. It was impossible to recognize anybody. Under the light of the moon they seemed the color of ivory."The lives of Yangel and a few other high ranking officials were spared since they had stepped into a bunker to take a break mere minutes before the explosion. Many others, including some of the most prestigious pioneers of the Soviet space program, were not so lucky. Among those killed were:

However, the true casualty list has always remained a mystery. More recent investigations have estimated the death toll as high as 200. The best estimate, however, appears to be around 122 fatalities. This value includes 74 killed in the blast and 48 who died over subsequent weeks from injuries due to burns or exposure to toxic chemicals. Of those killed, 84 were military officers or enlisted technicians while 38 were civilian engineers.

In determing the origin of the disaster, the commission ultimately concluded that,

"The direct cause of the accident was the shortcomings in the design of the control system, which allowed unscheduled operation of the of the EPK V-08 valve controlling the ignition of the main engine of the second stage during pre-launch processing. This problem was not discovered during all previous tests. The fire on the vehicle...could have been avoided if the reconfiguration of the current distributor into a zero position was conducted before the activation of the onboard power supply."The report went on to blame the massive death toll on the actions of those who ignored or did not enforce proper safety procedures. Those responsible put too much confidence in the safe performance of the R-16 rocket under extreme conditions without proper analysis to justify their decisions.

Before proceeding with the R-16 program, the commission recommended more extensive testing of the control system and a re-evaluation of the pre-launch sequence to improve safety procedures. Even so, the willingness of the Soviet leadership to risk sacrificing more lives in pursuit of their political goals is rather shocking. The commission went on to recommend repairing the launch pad within two weeks and resuming the test program as soon as November!

Despite this optimism, the next launch attempt was not made until February 1961, and it too ended in failure when the rocket crashed during flight. The R-16 program continued to suffer after the loss of so many of the nation's most experienced rocket engineers, and it was not until June 1963 that the missile was finally accepted for military service. The R-16 and improved R-16U remained in use until 1974 when the type was eliminated under the first Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT-1).

Perhaps one of the most remarkable aspects of what has commonly become known as the Nedelin Disaster or Nedelin Catastrophe is how successful the Soviet Union was in covering up the event. Marshal Nedelin is still regarded as a hero to the Russian people for his service during World War II, and his untimely death was explained away as an aircraft accident. Families of those killed in the disaster were never told the truth, though rumors of an accident did spread as people realized that so many rocket experts had died around the same time. Western observers occasionally heard some of these rumors from defectors, but the stories became mixed with other unrelated events and were never taken seriously. It was only after the fall of communism in 1990 that the true scope of the Nedelin Disaster finally became public.

Today, the location of the explosion at Site 41 is an empty and abandoned lot at the edge of the Baikonur

Cosmodrome. The site is marked only by a small monument containing the names of those who perished and a map

illustrating the layout of the old launch complex.

Elsewhere on the base is a single coffin containing the remains of those who could not be identified. The coffin

was buried in Leninsk Park and is now covered by a small grassy mound and fenced in. It was not until three years

after the disaster that local officials were allowed to erect a memorial obelisk over the site. The memorial lists

the names of 54 victims of the blast who were never identified. It is because of their needless sacrifice that 24

October 1960 will forever be remembered as one of the darkest days of the space race.

- answer by Joe Yoon, 6 June 2004

Related Topics:

Read More Articles:

|

Aircraft | Design | Ask Us | Shop | Search |

|

|

| About Us | Contact Us | Copyright © 1997- | |||

|

|

|||