|

||||||||||

| Location: Home > %7Eaerospa1 > ask a rocket scientist > spacecraft > q0288 | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Location: Home > %7Eaerospa1 > ask a rocket scientist > spacecraft > q0288 | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

The Space Shuttle program was first approved in 1972 and construction of OV-101 began at Rockwell International in Palmdale, California, in 1974. Enterprise was completed and rolled out of the assembly plant in 1976. The vehicle was originally supposed to be called Constitution in celebration of America's bicentennial, but a write-in campaign by fans of the television show Star Trek encouraged NASA to name OV-101 as Enterprise instead.

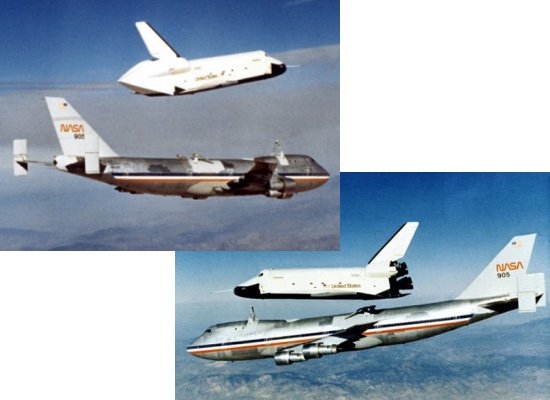

Enterprise was used for several ground vibration tests before being moved 36 miles (56 km) over land to NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center located at Edwards Air Force Base north of Palmdale. From February through October of 1977, Enterprise conducted a series of taxi and flight tests to demonstrate that the Orbiter design could operate from a conventional runway. Known as the Approach and Landing Test, or ALT, the program began with a series of three taxi tests while Enterprise was attached to the modified Boeing 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA). The taxi tests measured structural loads and responses to determine how well the mated vehicles could be handled and controlled on the ground up to speeds of 157 mph (253 km/h). The SCA's braking and steering systems were also tested.

Enterprise became airborne for the first time on 18 February 1977 as the second stage of testing began. These five flights were called captive-inert and had Enterprise remain mated to the SCA with no crew aboard. A tailcone was placed on the back of Enterprise to reduce turbulence on the tail control surfaces of the 747 while the two planes were attached. These flights reached altitudes up to 30,000 ft (9,145 m) and a maximum speed of 474 mph (763 km/h). The longest captive flight lasted over three hours, and this phase of testing allowed NASA to determine the structural integrity and handling qualities of the mated vehicles in flight.

Next came a series of three additional captive flights with two crewmen aboard Enterprise while it remained attached to the SCA. These flights allowed the crew to operate the systems and flight controls aboard Enterprise while it was in the air and verify that the vehicle functioned properly. This phase also included flutter tests of the mated craft at low and high speed, a separation trajectory test, and a practice for the first free flight.

At last on 12 August 1977, Enterprise was released from the SCA for the first time to fly and make a gliding landing on its own under astronaut control. A total of five free flights were conducted, the last two without the tailcone attached. Mockups of the three space shuttle main engines and two orbital maneuvering system engines were exposed for these two flights to simulate the Orbiter's aerodynamic configuration during a return from space. The longest free flight lasted nearly 5½ minutes after Enterprise was released from an altitude of 26,000 ft (7,925 m). The free flights were performed at minimum weight and various center of gravity locations as well as several release altitudes to test the Orbiter's flight characteristics under different conditions.

The first four gliding flights landed on the dry lakebed at Edwards AFB while the final test touched down on the main concrete runway to simulate a return from space. The free flights demonstrated the vehicle's approach and landing capabilities while under pilot control, an autoland approach mode, the airworthiness of the Orbiter design in subsonic flight, and the operation of several key systems in preparation for the first manned orbital flight. The final flight also revealed a problem in the control system that could allow Pilot-Induced Oscillation (PIO), a phenomenon where the pilot's control inputs result in the vehicle becoming unstable. Because this issue was identified so early, engineers were able to develop a correction for the control system years before the first orbital flight.

Two different astronaut crews flew aboard Enterprise during the captive and free flights. Five of the eight missions were flown by Fred Haise (of Apollo 13 fame) and Gordon Fullerton while the remaining three included Joe Engle and Richard Truly. The same crew of four was aboard the 747 SCA during all 16 taxi and flight tests. This crew included pilots Fitzhugh Fulton and Thomas McMurtry as well as flight engineers Louis Guidry and Victor Horton.

Following its final free flight on 26 October 1977, Enterprise was transferred to several other NASA facilities for additional tests preparing the way for the first Space Shuttle launch. Modifications were first made to the SCA and Enterprise for a series of four ferry flights to various NASA facilities. OV-101 was then ferried to NASA Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, in 1978. At Marshall, Enterprise was mated to an External Tank (ET) and two Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) so the assembled stack could undergo vertical ground vibration tests. The tests measured structural dynamic response modes of the mated vehicle that were used to refine the design of connection interfaces. Enterprise was next ferried to NASA Kennedy Space Center where it was again mated to an ET and SRBs. The combined stack was transported on the mobile launcher platform to Launch Complex 39-A for fit checks and to practice launch and handling procedures. Finally, Enterprise was brought back to NASA Dryden in 1979 where the Orbiter was again moved over land to the Rockwell International factory. Here, several components were removed and refurbished for installation on the spaceworthy Orbiters under construction.

The first orbital mission of the Space Shuttle was launched in April 1981 when Columbia (OV-102) made the maiden journey into space. Originally, it was planned that Enterprise would be modified with the same systems as Columbia and converted into a spaceworthy Orbiter. Although Enterprise resembled the other Orbiters externally, it had not been built with working engines, orbital maneuvering thrusters, or thermal protecting tiles. These systems were to be refitted so that Enterprise would be the second Orbiter to be launched into space. However, the Orbiter design was revised as Columbia was being built to save weight. Many changes would have to be made to the wing and fuselage structure of Enterprise to make it compatible with the rest of the Shuttle fleet.

NASA decided this conversion was too expensive. A cheaper alternative was to modify another test vehicle called Static Test Article 099 (STA-099) into a spaceworthy orbiter. Once converted, STA-099 became OV-099 and was named Challenger. Thus, Challenger became NASA's second spaceworthy Orbiter and was joined by Discovery (OV-103) and Atlantis (OV-104) to create a fleet of four Shuttles. Enterprise, meanwhile, was essentially retired. The Orbiter was ferried around the world in 1983 to make appearances in France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Canada. Enterprise was also transported by barge from Mobile, Alabama, to New Orleans, Louisiana, for the 1984 World's Fair. One of the vehicle's final official uses came in 1985 when Enterprise was ferried to Vandenburg Air Force Base in California. The US Air Force had originally planned to launch Space Shuttle flights from this west coast site to achieve polar orbits. Enterprise was attached to an ET and SRBs and rolled out to the SLC-6 launch pad for fit checks and other tests. Plans to launch the Shuttle from this site were later abandoned and no other Orbiter ever visited SLC-6.

Enterprise was officially retired on 18 November 1985 when the vehicle was ferried to Washington, DC, and donated to the Smithsonian Institution National Air & Space Museum. After the Challenger disaster in 1986, NASA again explored converting Enterprise into a spaceworthy replacement, but it was decided to instead build a new Orbiter from spare structural parts that had been purchased with Discovery and Atlantis. These components were used to construct OV-105 that was given the name Endeavour.

Enterprise remained in storage at the Smithsonian's Dulles Airport facility throughout the 1990s but parts of it were removed for use in the investigation that followed the loss of Columbia in 2003. Fiberglass panels along Enterprise's wing leading edge simulated the reinforced carbon-carbon (RCC) thermal protection panels of Columbia. Panels taken from Enterprise were used in a series of tests to evaluate the damage a foam insulation impact could do to the thermal protection system. These tests as well as tests on actual RCC panels removed from Discovery demonstrated that a foam impact could indeed create cracks or holes in the RCC panels, which was the most likely cause of the Columbia disaster.

Enterprise remains part of the Smithsonian collection today and is now the featured attraction of the space

collection displayed at the National Air and Space

Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center near Dulles International Airport.

- answer by Molly Swanson, 7 January 2007

Related Topics:

What has become of the HOTOL re-usable rocket concept?

Read More Articles:

|

Aircraft | Design | Ask Us | Shop | Search |

|

|

| About Us | Contact Us | Copyright © 1997-2025 | |||

| Location: Home > %7Eaerospa1 > ask a rocket scientist > spacecraft > q0288 | |||

|

|

|||