|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

Since the loss of the Space Shuttle Columbia in 2003, we have received many questions about the foam used on the Shuttle's External Tank. These questions have continued as NASA has struggled to eliminate the problem of foam shedding during subsequent return to flight missions. Several of the more common questions are addressed in this article.

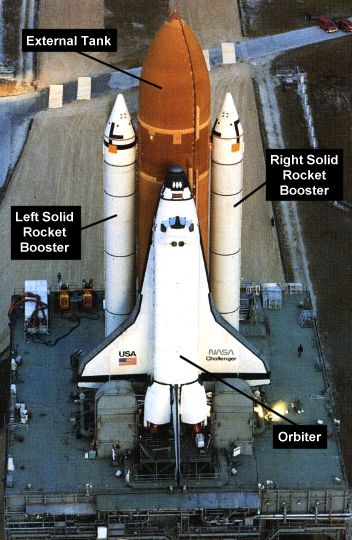

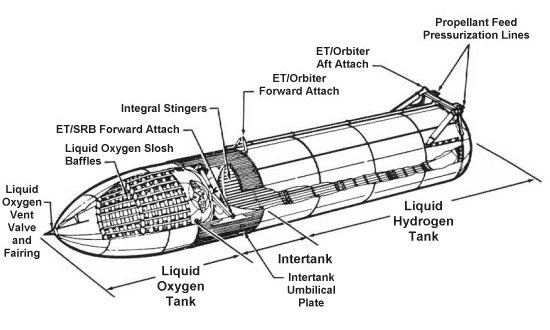

The tank is made up of three major sections. At the top is a tank containing liquid oxygen used as an oxidizer in the main engines. At the bottom is a tank for liquid hydrogen burned as fuel by the main engines. In between these two sections is a region called the intertank that contains various instrumentation and processing systems for the propellant tanks.

Both oxygen and hydrogen exist as gases at standard temperature and pressure. Since their density in this state is quite low, the amount of these substances required by the Space Shuttle would take up an enormous volume. The only way to carry sufficient propellant in a reasonable amount of space is to increase the density of the gases by cooling and pressurizing them until they become liquids. The liquid oxygen is cryogenically cooled to -300°F (-184°C) while the liquid hydrogen is chilled to -423°F (-253°C). These liquids must be kept at high pressure and very low temperature or they will boil back to a gaseous state.

As the Space Shuttle rises through the atmosphere, however, the outer surface of the tank is heated by friction with the external air that rushes past the vehicle at very high speeds. A thermal insulation coating is needed on the outer surface to maintain a constant temperature inside. Without this insulation, the cryogenic fuels would become warmer and start to convert back into a gas, raising the pressure inside the tank and possibly causing it to disintegrate. The thermal insulation is a 1 inch (2.5 cm) thick polyisocyanurate foam sprayed on the outer surface of the tank.

This insulation is also important for reducing the formation of ice on the outside of the tank while it is sitting

on the pad prior to launch. Ice has always been one of the greatest concerns of NASA engineers since it would

likely fall off the tank during launch and could impact the Orbiter. Large chunks of ice can be very heavy and

dense, so any impacts against the heat tiles on the lower surface of the Orbiter could easily damage these critical

surfaces.

- answer by Justine Whitman, 17 December 2006

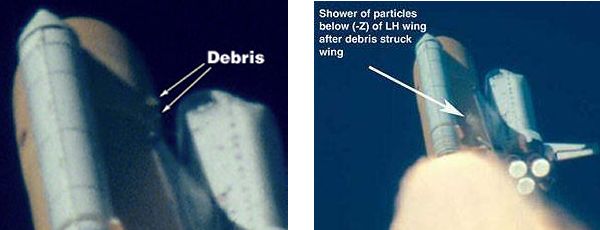

To determine whether a coat of paint might prevent foam from shedding requires a better understanding of what causes the foam to fall off in the first place. Most people probably assume that the foam separates from the tank because the flow of air rushing past rips it away. This type of separation is called an adhesive failure because the foam does not properly stick to the bare aluminum surface of the tank. However, NASA research has found that very little, if any, of the foam comes off because of adhesive issues.

The problem is instead caused by a cohesive failure. In other words, the foam itself does not stay together. This cohesive failure is caused by voids created inside the foam as it is sprayed onto the tank. These voids create pockets of air trapped within the foam. Since the voids are formed at sea level, the air inside them is at sea level pressure. As the Shuttle climbs into orbit, the external atmospheric pressure continually decreases. This difference causes the relatively high pressure air trapped inside the foam to expand outward ripping off chunks of foam in the process. Further worsening the problem is the heat generated by friction between the thermal insulation of the tank and the air rushing past it as the Shuttle accelerates to high speeds. This effect heats up the air pockets within the foam raising the pressure and further encouraging the voids to rupture. This phenomenon is often referred to as "pop-corning."

Since the problem lies deep inside the foam rather than at its surface, an outer coating of paint would do little

to stop this process. NASA records support this conjecture since the first two missions flown with a painted

External Tank suffered just as much foam loss as those with an unpainted tank. Indeed, it is more likely that an

extra coating on top of the foam would end up creating an even bigger problem by adding chunks of paint to the

debris threatening the Orbiter.

- answer by Jeff Scott, 17 December 2006

Whether this netting was an internal or external addition to the thermal coating, any such solution would require a

great deal of research, testing, and new manufacturing techniques. Any change to the Shuttle is subject to a very

lengthy and rigid certification process to understand what unintended effects it might have on the vehicle. This

particular change would require exploring if and how the netting could fail, how much mass it might have, and how

it might threaten the Orbiter. NASA has concluded that such a process would take several years and probably would

not be completed before the Space Shuttle is retired in 2010. Instead, NASA has focused its efforts on improving

the foam application process to minimize voids while also identifying and eliminating other potential debris

sources elsewhere on the vehicle.

- answer by Jeff Scott, 17 December 2006

Read More Articles:

|

Aircraft | Design | Ask Us | Shop | Search |

|

|

| About Us | Contact Us | Copyright © 1997- | |||

|

|

|||