|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

Earhart the Record-Setter

Amelia Earhart was born in 1897 and was just shy of her 40th birthday when she was lost. Earhart was first exposed to aviation in 1920 when she was given a ride by an air racer and became immediately entranced by flying. She soon began lessons from another female aviation pioneer named Neta Snook and purchased her own plane. Despite stalling and crashing her first aircraft during one takeoff attempt, Earhart became just the sixteenth woman in the world to be issued a pilots license by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) in May 1923.

Even before earning her license, Earhart was already striving to set the aviation records that would make her famous. In 1922, she reached a world record altitude for a woman pilot of 14,000 ft (4,265 m). Health troubles curtailed her flying during the next few years but she was a passenger on a famous transatlantic flight in 1928. Her involvement in the event was extensively promoted by the press, including a publisher named George Putnam whom she would later marry. Though Amelia was rather embarrassed by the attention since she played no role in flying the plane, the exposure earned her lucrative endorsement deals to finance further flights. Earhart was soon competing in air races, setting new altitude records, and promoting greater freedoms for female pilots.

Earhart's fame continued to grow when she became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean in 1932, just the second solo flight across the ocean after Charles Lindbergh's. She also completed several record solo flights in 1935 as the first person to fly from Honolulu, Hawaii, to Oakland, California, the first from Los Angeles to Mexico City, and the first from Mexico City to New York. Amelia planned to top these successes with her biggest challenge yet of flying around the world in 1937, after which she expected to end her long-distance flying career.

The World Flight

Earhart retired the Lockheed L-5B Vega she had used on earlier flights in favor of a new Lockheed L-10E Electra capable of greater distances. Though her World Flight would not be the first to circle the Earth, hers would be the longest to date since she planned to follow a path near the equator. During the trip, she would also collect photos and information for publication in a book about her adventure--the material collected up to her disappearance was published under the title Last Flight. Given the distance and difficulty of the journey, Earhart needed a navigator to help chart her course. She ultimately chose the 44 year-old Fred Noonan who had extensive experience both in ship and aircraft navigation. Noonan had previously worked for the airline Pan Am where he charted the routes used by the company's flying boats across the Pacific.

The journey was originally intended to leave California and head west across the Pacific. Only one leg of the flight was completed from Oakland to Hawaii on 17 March 1937 when Earhart made an emergency landing due to problems with the variable-pitch propellers. Following repairs, Earhart attempted to takeoff but the plane went into a ground loop either because of a tire blowout or pilot error. The Electra suffered extensive damage that forced Earhart to abandon the world flight and ship the plane back to the factory for major repairs.

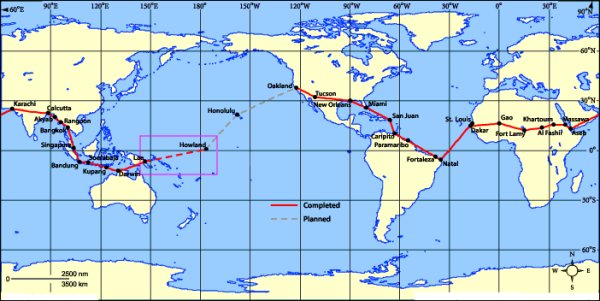

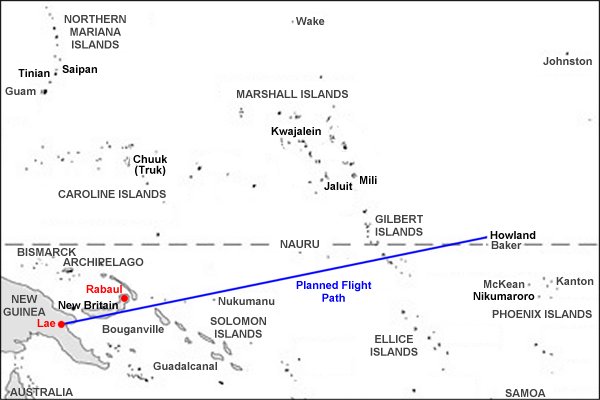

While Earhart and her husband George Putnam collected additional money to fund a second attempt, the route was reversed to fly eastward and take advantage of winds expected at that time of year. Aboard their newly repaired Lockheed Electra, Earhart and Noonan departed Oakland on 20 May 1937 for Miami where the world flight was officially announced to the public. The pair departed Miami on 1 June covering some 22,000 miles (35,400 km) while making stops in South America, Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and Australia before arriving at Lae, New Guinea, on 29 June. The remaining 7,000 miles (11,300 km) of the flight would cross the Pacific with refueling stops on tiny Howland Island and Oahu before returning to Oakland.

Searching for Howland

Earhart and Noonan left Lae on the morning of 2 July headed northeast to uninhabited Howland Island where they were to meet with the US Coast Guard cutter Itasca for fuel and rest. Howland is only 6,500 ft (2,000 m) long by 1,600 ft (500 m) wide and difficult to spot from the air, so Earhart and the Itasca had arranged to communicate by radio for guidance. Unfortunately, two-way communication was never successfully established. The Itasca could receive Earhart but she was apparently unable to hear the vessel. Either her radio gear had failed, and there is evidence an antenna on the bottom of her plane was damaged as it departed New Guinea, or she did not understand how to operate the plane's direction finding antenna, which was a very new technology.

Further compounding the problem was Earhart and the Itasca using clocks that differed by a half hour throwing off the anticipated communication schedule. Earhart may not have been listening at all when the ship was sending and, during other instances, the two may have been transmitting at the same time preventing them from hearing each other. The Itasca crew also reported that Earhart's tranmissions were too short and too weak to get a fix on her location.

Frustrated by the lack of success, the ship requested she switch to more powerful Morse code better suited to direction finding. Unknown to the cutter, Earhart had the Morse radio and its antennas removed from the Electra during its repair since she disliked using the equipment and neither she nor Noonan was proficient in Morse code. Itasca also attempted to create a plume of smoke for the aviators, but weather conditions reduced its visibility and the flyers apparently never saw it.

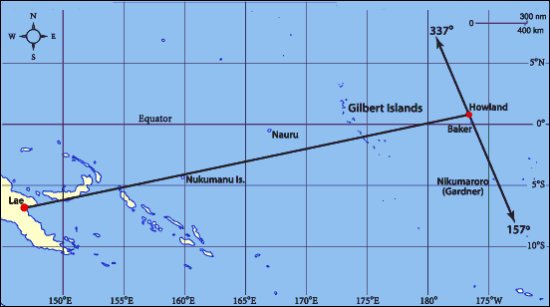

As radio transmissions faded, the Itasca lost contact with Earhart and Noonan and it became clear the Electra was flying away from the vessel. The pair should have landed on Howland between 6:30 and 8:00 AM but their final known transmission was received at 8:45. Earhart indicated, "We are on the line 157 337... we are running on line north and south..."

The Itasca continued to transmit for another hour before concluding Earhart and Noonan must have ditched at sea. Search procedures began, and it was estimated the plane had gone down 35 to 100 miles (55 to 160 km) northwest of Howland Island due to overcast conditions in that direction. President Franklin Roosevelt authorized a search effort costing over $4 million and involving ten ships, 66 aircraft, and over 3,000 Navy personnel. The search covered 262,280 square miles (679,300 sq km) but was unable to find any trace of Earhart, Noonan, or their plane. The effort was discontinued two weeks later on 19 July. George Putnam finally gave up hope in October and Amelia Earhart was officially declared dead on 5 January 1939. Fred Noonan had been declared dead in June 1938.

Crash-and-Sink Theory

Now seventy years since their disappearance, the fate of the famous flyers remains an unsolved mystery. A number of theories have emerged to explain what became of them, but these fall into three general categories. The first and most accepted theory is that Earhart ran out of fuel and ditched the Electra at sea near Howland Island. If so, the aircraft most likely sank within minutes. The aviators may have been able to escape, but it is believed they had left behind any rafts or other emergency gear to save weight.

A researcher named Elgen Long believes weather systems in the region caused the pair to misjudge their course and fly further north of Howland Island than they realized. Based on the Itasca's radio log that records the strength of Earhart's signals, it is believed the aviators were flying a ladder search pattern as they sought Howland Island. Fred Noonan would have used celestial navigation techniques and the angle of the Sun to locate an instrument navigation reference called the "157/337 line of position" that should have brought the aircraft directly over the island. Earhart's final communications indicate she was following this procedure, and Long believes she would have found the island had she not run out of fuel. Furthermore, he believes that once the engines failed, the plane probably nosedived into the ocean given the high drag produced by the windmilling propellers. The flyers most likely died on impact or drowned as they tried to flee the sinking hulk.

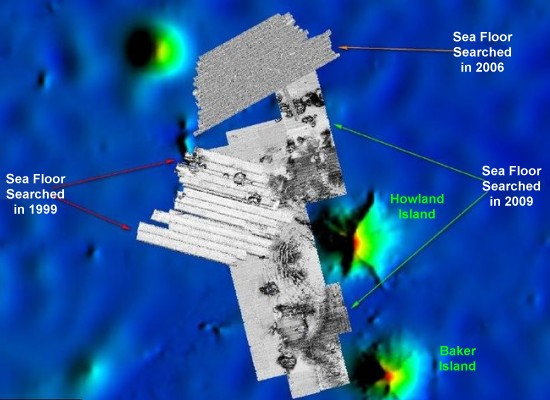

The only way to prove Earhart crashed at sea is to locate the wreckage of the Electra on the ocean floor, approximately 17,000 ft (5,200 m) deep. Several attempts at such a search have already been made. The first came in 1999 when investors Dana Timmer and Guy Zajonc financed the deep sea search firm Williamson and Associates to conduct a sonar survey of 2,000 square miles (5,200 sq km) northwest of Howland Island. The search area was based on Elgen Long's research but was unsuccessful. Long himself worked with another deep sea company called Nauticos to conduct a separate search in 2002, also without success. Nauticos tried again in 2006 but no evidence of the Electra was found.

Gardner Castaway Theory

An opposing collection of theories states that Earhart and Noonan crash landed on or near another island in the Pacific and may have survived as castaways for some length of time. Each of these theories depends on assumptions about how much fuel remained aboard the Electra at the time of Earhart's last transmission and what she would do if unable to find Howland Island.

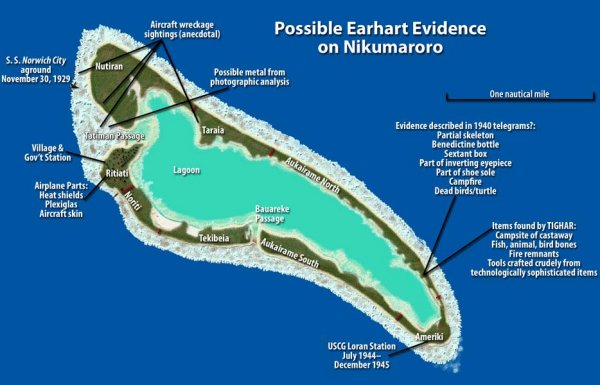

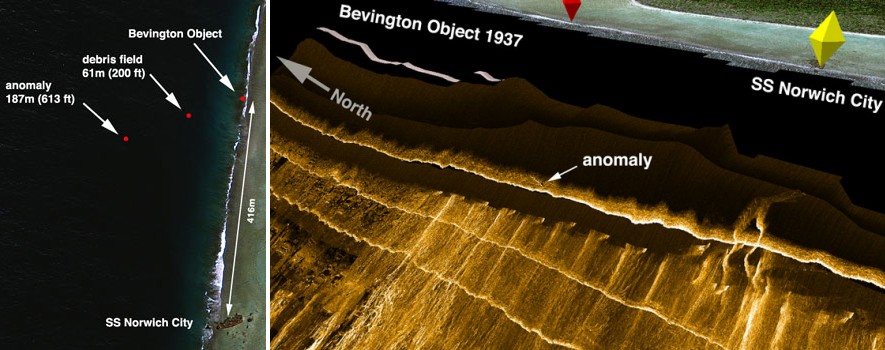

A group called The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) believes Earhart and Noonan most likely turned southeast along the 157/337 line of position since this choice gave the highest probability of finding land. By TIGHAR's calculations, the Electra carried enough fuel for approximately 24 hours flying time and reached the vicinity of Howland Island about 20 hours after takeoff, leaving some four hours worth of fuel to travel as much as 500 NM (925 km). If the pair had turned northwest along the 157/337 line, they had insufficient fuel to fly anywhere but Howland. If they turned southeast, however, the flyers would either locate the island or could continue to the Phoenix Islands group. TIGHAR believes flying in this direction brought Earhart near Gardner Island, now called Nikumaroro, about 350 NM (650 km) from Howland and within her remaining fuel supply. Nikumaroro is much easier to spot from the air than Howland given its size, large lagoon, and the wreckage of a freighter called the SS Norwich City that ran aground in 1929. Nikumaroro also features a large smooth reef where a plane could attempt an emergency landing.

Evidence that Earhart survived includes well over a hundred reports of radio transmissions received long after her plane must have ran out of fuel. While many of these reports have been discounted as hoaxes or misunderstandings, several may be legitimate. A radio station on the island of Nauru was among locations to hear the transmissions. The station sent a telegram to the US Secretary of State on 3 July stating it had heard Earhart's flight reports and continued to receive signals into the evening after she went down. The telegram described reception as "Fairly strong signals, speech not intelligible, no hum of plane in background, but voice similar to that emitted from plane in flight last night." The mysterious signals were detected on islands and ships throughout the Pacific, and perhaps even as far as the east coast of North America on harmonic frequencies, for about five days after the disappearance. If these transmissions did in fact come from Earhart, they suggest the plane must have been on land since the radio could only function while the Electra's right engine was running to power the batteries.

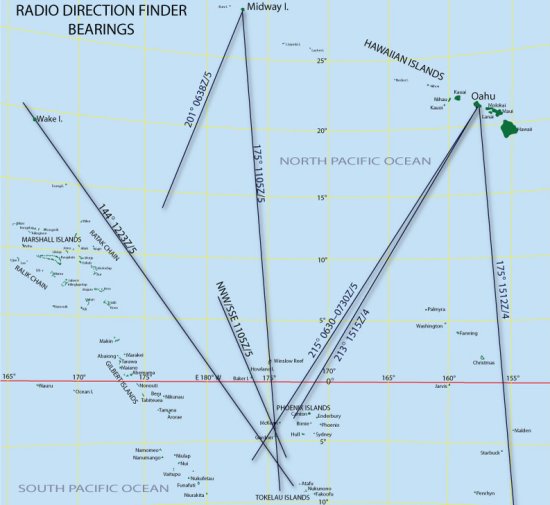

Most of the reported transmissions were too weak and unintelligible to be deciphered, but a few tantalizing clues include comments like "... ship on reef... south of equator..." and "...don't hold... with us much longer... above water... shut off..." The references to a ship on a reef and being south of the equator both match Nikumaroro, but the broadcasts were mysteriously separated by hours of silence. A possible explanation came from TIGHAR researchers who suspected the Electra might have landed on a reef covered by water at certain times of day making it possible to use the radio only when the tides were low enough. Further evidence comes from Navy and Pan Am stations on Wake, Midway, Howland, and Oahu that took bearings on the mysterious transmissions and suggested they emanated from the vicinity of the Phoenix Islands.

Nikumaroro was uninhabited at the time of Earhart and Noonan's disappearance but was part of the British Empire. In late 1938, the British dispatched a party to survey the island, and additional settlers from the Gilbert Islands had established a small colony within a year. Under the oversight of British colonial officer Gerald Gallagher, settlers cleared parts of the island to construct a village and plant coconut trees. Reports soon emerged of airplane debris found north of the shipwreck on the reef near "where the waves break." The waves had smashed the wreckage and eventually scattered it across the reef and shoreline, pushed it into the lagoon, or pulled it over the reef's edge onto the deep ocean floor below. Pilots who flew over the island in 1937 and 1938 as well as New Zealand sailors who visited Nikumaroro during that period also describe signs of recent habitation even though no colonists had yet arrived.

Tantalizing clues also come from telegrams sent by Gerald Gallagher to his colonial superiors. Gallagher said he and the settlers had found a partial human skeleton, pieces of a woman's shoe, a sextant box, part of a sextant eyepiece, and a bottle near an apparent campsite under a tree on the southeast corner of the island. Curiously, this is the opposite end of the island from the shipwreck where aircraft wreckage was supposedly found but was close to a food supply. Gallagher suspected the skeleton was the remains of Amelia Earhart and had it transported to Fiji for study. Two medical examinations were conducted with the first concluding the skeleton belonged to an elderly Polynesian male and the second suggesting it was a short, stocky European male. The bones have since disappeared, but the notes and measurements taken during the second examination survive. A 1998 review of these measurements by forensic anthropologists concluded the remains were more likely to belong to a female of northern European ancestry between 5'5" and 5'9" in height, consistent with Amelia Earhart, but the level of confidence was low given the lack of actual remains for analysis.

In searching for additional evidence, TIGHAR has conducted several expeditions to Nikumaroro since 1989. The island has been uninhabited since 1963 but the expeditions have uncovered numerous artifacts that may date to the 1930s. Items found by TIGHAR include parts of a shoe that may match a type Earhart was known to wear (though the manufacturer says the sole belongs to a size 10 shoe and Earhart is believed to have worn a size 6), fragments of bottles and a cap, pieces of glass and metal that appear to have been used as crude tools, and aircraft debris. These plane parts include a section of aluminum skin, Plexiglas matching an Electra's cabin windows, and metallic components that may be heat shields from the cabin of a civil aircraft. While TIGHAR has uncovered suggestive clues that Earhart and Noonan reached Nikumaroro, none of the items found can be conclusively tied to their ill-fated flight. The group continues to visit the island hoping to locate human remains for DNA testing or debris with a serial number that can be matched to the Lockheed Electra.

New Britain Crash Theory

While the Nikumaroro hypothesis assumes Earhart and Noonan did a good job of navigation and knew generally where they were, other theories usually rely on the pair making major errors because of weather conditions. Stronger than expected headwinds and extensive cloud cover preventing star sightings are the most frequent weather phenomena assumed by these explanations. The following theories also speculate the aviators quickly gave up searching for Howland Island and, rather than remain on the 157/337 line, reversed course and turned back in the direction they'd come from. Backtracking to the west or northwest would bring the Electra over the Gilbert Islands, ranging from 450 to 650 NM (825 to 1,200 km) from Howland, where Earhart could try landing on a reef. This was her contingency plan according to Gene Vidal, director of the Bureau of Air Commerce who had helped coordinate Earhart's flight.

One such theory has been promoted by Australian engineer David Billings who believes Fred Noonan misjudged the Electra's position because of high winds and his inability to take celestial navigation fixes during the flight. Billings uses these factors to suggest the plane was actually considerably short of Howland Island when the flyers began searching for it, perhaps by hundreds of miles. Billings further cites data on the Electra's fuel consumption rates showing the plane was more efficient than assumed by most researchers, suggesting the plane could have reversed course and flown much farther than is generally believed.

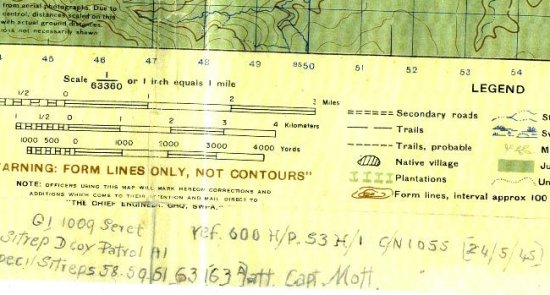

Rather than landing in the Gilberts, however, this theory places the wreckage of the Electra far to the west about 1,900 NM (3,500 km) from Howland. The hypothesis is based on reports from Australian soldiers who stumbled across unidentified aircraft wreckage on the island of New Britain during the closing months of World War II. The island was administered by Australia at the time of the Earhart disappearance, but Japan invaded East New Britain in 1942 and held this part of the island for most of the war. It was not until 1945 when Australia launched an offensive to liberate the region. While on patrol, a group of soldiers discovered a radial engine nearly swallowed by jungle growth. Nearby, a second engine was found still attached to the wing and fuselage of an unpainted aircraft. The wreckage was in poor condition and so corroded it was considered too old to be a World War II plane. The cockpit was also crushed making it unlikely anyone aboard survived the crash. The soldiers took an identification tag from the detached engine but otherwise left the wreck undisturbed as they continued their mission.

The engine mount tag and the report of its discovery were sent to higher authorities in hopes of identifying the wreckage. The information was apparently sent to the US Army Air Forces that responded the engine did not belong to any of its aircraft and may have been part of a civilian plane. A map prepared by the Australian unit that found the wreckage contains notes referring to "600H/P S3H/1 C/N1055" that are believed to be details from the tag. These somewhat cryptic comments are reminscent of Earhart's Lockheed Electra that had the construction number C/N 1055 and was powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-1340-S3H1 Wasp engines rated at 600 horsepower. The tag has since gone missing, but it is nevertheless an intriguing clue since no twin-engine plane using Wasp engines is known to have been lost in that part of the world except Amelia Earhart's.

Based on this evidence, the group Electra Search Project on New Britain believes the soldiers accidentally found the wreck of Amelia Earhart's plane and possibly her final resting place. Billings suggests Earhart and Noonan, having failed to locate Howland Island, reversed course and flew back towards New Guinea. The aviators apparently passed by the Gilbert and Solomon Islands believing they had enough fuel to reach an island with a runway. Landing on a runway would surely be preferred over forcing the plane down on a reef to reduce the risk of injury and aircraft damage, but airfields were few and far between in the Pacific Ocean at the time. The closest runway was rather distant at Rabaul on New Britain.

If this theory holds true, the flyers obviously did not reach Rabaul but crashed some 40 miles (65 km) away on a hillside in the Mevelo River valley according to the Australian map. The Electra Search Project has led several expeditions into the jungles of East New Britain since 1993 trying to locate the mysterious wreck and determine its true identity. Success has been elusive and the search has been frustrated by thick jungle nearly impossible to penetrate. If able to raise sufficient funding, plans for a future attempt include using a helicopter equipped with a magnetometer to find large metallic objects in the dense growth.

Japanese Prisoner Theory

Alternate theories about the fate of Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan that became popular during World War II instead speculate the two were taken prisoner by Japan. The Japanese government has steadfastly denied any involvement in the Earhart disappearance, but several variations of the rumors continue to persist. The stories begin with the suggestion that Earhart and Noonan landed on or near a Japanese island, were shot down by the Japanese, or were purposefully spying on Japan at the request of the Roosevelt administration. This last theory was popularized by the 1943 movie Flight for Freedom that starred Rosalind Russell as a female pilot making a flight around the world. The pilot was instructed to "disappear" over Japanese territory giving the US Navy an excuse to search the area and observe the pre-war build up at Japanese military installations.

No evidence has been found to substantiate that Earhart was working for the US government, and her strong pacifism makes a spy mission for the military unlikely. Even if Earhart had the time and fuel to make a detour over Japanese islands, she would have been in the area at night when she wouldn't have been able to observe any targets of interest. Nevertheless, her friend Jackie Cochran visited Japan after the war where rumors suggest she found files discussing Earhart. Cochran herself denied this claim and stated she was convinced Japan had nothing to do with Earhart's loss, but a variety of theories have speculated Earhart was captured as a spy and may have been used for propaganda purposes. Some believe, for example, that Earhart was one of the women serving as the infamous Tokyo Rose whose English radio broadcasts were used for psychological warfare against American military personnel. Earhart's husband George Putnam listened to several Tokyo Rose recordings but could find none that he believed matched Amelia's voice.

Another bizarre theory related to the spy rumors was promoted by a retired Air Force officer named Joseph Gervias who concluded Jackie Cochran had discovered Earhart alive in Japan and smuggled her back to the US. Earhart was given a new identity, for reasons of national security, and she became a New Jersey housewife named Irene Bolam. Bolam adamantly denied the tale and Earhart's relatives found it to be "absurd," but Mrs. Bolam became a media sensation after Joe Klaas and Gervias wrote a book about her in the 1970s. The publisher eventually pulled the book from stores after Bolam sued the authors. The cause was resurrected in 2003 by Rollin Reineck who published his own book about Bolam after her death. However, most researchers have discounted the Bolam theory after studies by forensic experts comparing photos of her and Earhart concluded they were not the same person.

Like the New Britain premise, the Japanese prisoner theories cite Gene Vidal's statement about Earhart's contingency plan to turn northwest toward the Gilbert Islands. If they were far enough north of Howland Island before reversing course, however, the turn westward would not have brought the plane to the Gilberts but instead over the southern end of the Marshall Islands. At the time, the Marshall Islands were held by Japan under a mandate from the League of Nations. If American pilots happened to show up in these strategic Japanese possessions in the tense pre-war environment of the late 1930s, some researchers suggest they would have been captured as spies no matter how innocent their intentions had been.

Evidence of Earhart and Noonan becoming Japanese prisoners comes from residents of these and other islands administered by Japan as well as US servicemen who served in the Pacific during the war. Natives of the Marshalls and the island of Saipan in the Marianas much further west have told tales of two American aviators, a man and a woman, being held there around 1937 to 1939. While it is virtually impossible the Electra could have flown all the way to Saipan, it is conceivable Earhart and Noonan landed in the Marshalls and were brought to Saipan.

The Japanese prisoner theories rely on such native stories to piece together Earhart's movements through the Pacific. Based on this collection of tales, researchers believe the Electra crash-landed at the Mili Atoll about 760 NM (1,400 km) from Howland Island. Earhart and Noonan were later picked up by a Japanese fishing boat or naval vessel after waiting several days. An Imperial Navy survey ship called the Koshu was in the Marshalls a week after Earhart's disappearance and is said to have steamed to Mili to pick up the two flyers and their damaged aircraft. The pair were then taken to another island, probably Jaluit, where Noonan received medical treatment for injuries received in the crash. The two were moved again to Kwajalein and ultimately imprisoned at Saipan.

In 1960, a woman named Josephine Akiyama who had lived on Saipan came forward suggesting she had seen two Americans being held on the island in 1937. Four other native women also told stories of a thin foreign woman with short hair cut like that of a man who was on Saipan around the time. They said the woman had been a pilot who was captured spying after her plane crashed to the south. Additionally, some of the women remembered excitement about an aircraft with a broken wing being transported aboard a Japanese ship. The natives also said the foreigner was kept under guard and looked sickly. They went on to suggest the woman was either killed or died of illness and was buried on the island.

These stories caught the interest of a CBS Radio correspondent named Fred Goerner who traveled to Saipan in the 1960s looking for evidence to solve the Earhart mystery. While some 50 residents claimed to remember two American aviators, no official documentation of their presence could be located. Goerner hired divers to search Saipan's harbor for aircraft wreckage, but the only debris was from a Japanese plane and not the Electra. Goerner also looked into rumors from a US Army sergeant named Thomas Devine who said he was shown graves of the two flyers while stationed on Saipan in 1945. Although bodies were uncovered, they did not match those of Earhart or Noonan. Goerner went on to contend that US servicemen actually recovered the pair's bodies which may still be in the possession of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology today. He also maintained that his theories were confirmed by no less than the famous Admiral Chester Nimitz who commanded the US Pacific Fleet during the war.

More recent researchers have elaborated on Goerner's work. In particular, several American soldiers have shared their own recollections of Earhart-related discoveries on Saipan. Robert Wallack was a Marine who stated he found Amelia's briefcase containing her papers in the safe of a Japanese officer after the island was liberated. Another Marine named Earskin Nabers further states he received a message about Earhart's aircraft being found in a Japanese hangar at Aslito Airfield and was told to guard it. The aforementioned Thomas Devine says he inspected the Lockheed Electra, noting the registration number NR16020 of Earhart's plane, and later watched as it was purposefully burned by American soldiers. (Although it is odd Devine revealed none of this information when assisting Fred Goerner with his book.) Devine claims the act was performed under the direct supervision of Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal who was covering up evidence of Earhart's disappearance to protect Pres. Roosevelt.

Despite the inability to find compelling evidence placing Earhart and Noonan on these islands, at least a dozen expeditions to the Marshalls and Marianas have continued seeking clues to the fate of the famous flyers. One expedition was to the island of Tinian just south of Saipan. A US Marine named Saint John Naftel who was stationed on the island in 1945 says he was shown two graves where the Japanese had supposedly executed and buried Earhart and Noonan. Archaeologist Jennings Bunn tested the theory by organizing an excavation of the site, but no remains were found. Additional excavations have been conducted elsewhere on Saipan near locations where rumors suggest the aviators were held, but no trace of their remains have turned up. Still other rumors place the pair on the island of Truk (now called Chuuk) or at a prisoner of war camp in the Philippines, China, or mainland Japan.

Conclusion

While some of these theories may appear more likely than others, the lack of any conclusive evidence makes it

impossible to completely eliminate any of them. Variations of the three main types of theories all sound

plausible. Ditching at sea seems the simplest and most likely explanation, but what of the evidence of aircraft

wreckage or possible radio transmissions received days after the plane went down? A crash landing on Nikumaroro to

the south, New Britain to the west, or the Marshall Islands to the north could be possible given the fuel capacity

of the Electra and differing assumptions on how quickly it was used. There are also plenty of native stories and

other circumstantial evidence suggesting Earhart and Noonan might have survived after their disappearance.

Unfortunately, the mystery will be impossible to solve until human remains or aircraft parts are found that can be

irrefutably linked to the aviators or their plane. Given the length of time that has passed since Amelia Earhart

and Fred Noonan vanished over the Pacific, the question remains whether any such evidence still exists.

- answer by Molly Swanson

- answer by Jeff Scott, 25 March 2007

Update!

Since this article was originally written, additional research into several of the disappearance theories has been underway. In fact, the number of Earhart search expeditions seems to grow every year!

In 2009, the Waitt Institute for Discovery conducted the largest exploration to date of the sea floor around Howland Island. The group performed a detailed sonar survey of 2,200 square miles (5,700 sq km) to the north and west of the island but located no trace of Earhart's Electra. The team also produced an excellent archive of its research at the site Search for Amelia.

Two more groups are raising funds for their own deep sea searches. Explorer Dana Timmer has launched The Expedition for Amelia hoping to again employ Williamson and Associates in exploring targets identified in previous surveys. A rival team called The Stratus Project is led by Colin Cobb who manages Earhart and Titanic related sites in Ireland. This group has identified an area overlooked by other sonar searches where they believe the Electra will be found.

The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) has completed additional expeditions to the island of Nikumaroro and is raising funds for another. The research team has found further evidence suggestive of a castaway including parts of a zipper and snap, pieces of mirror like that found in a woman's compact, various bottles and other debris apparently from women's cosmetics, and parts of a broken pocket knife of American manufacture. The findings are reportedly consistent with the 1930s, but none of the items can yet be conclusively connected to Amelia Earhart. The group also found bone fragments that may come from a human finger, perhaps related to the skeleton Gerald Gallagher reported in 1940. TIGHAR had the remains DNA tested for comparison to Earhart's relatives but the results were inconclusive.

Most ambitious of TIGHAR's recent efforts have been underwater surveys along Nikumaroro's northwestern reef where the group believes wreckage from the Electra may be found. Although suggestions of a debris field may indicate the plane's path as it slid down the reef, definitive aircraft wreckage remains to be discovered. Many difficulties have been encountered using remotely-operated sonar and camera equipment in the hostile environment, so TIGHAR plans to use manned submersibles in its next attempt. If successful, TIGHAR hopes to locate, photograph, and possibly recover debris from Earhart's Lockheed Electra.

The Electra Search Project on New Britain continues efforts trying to locate the mysterious wreckage in the New Guinea jungle. The most recent attempt came in late 2012 but was cut short due to difficult terrain, bad weather, and equipment troubles. Team leader David Billings has also suggested the debris is most likely buried after years of landslides in the seach area. The project seeks investors to fund a magnetometer search by helicopter to locate buried metallic objects.

Similar theories about Earhart's plane ending up in Papua New Guinea have emerged following discoveries of wrecks in the region. Rumors circulated in 2009 that aircraft debris found in the Ip River in East New Britain could be the legendary Electra. The few details provided are instead suggestive of an American military plane lost during World War II. Another flurry of excitment came in early 2011 when residents from the island of Buka near Bougainville announced finding the underwater wreck of a twin engine aircraft. A diver to the site reportedly discovered two human skulls and boxes of gold bullion aboard. Although the location lies near Earhart's path from Lae to Howland, it's highly unlikely she had any cargos of gold onboard! A World War II aircraft is more likely, possibly a Japanese plane trying to escape with war booty if there is any truth to the gold rumor. Further dives on the wreck, 230 ft (70 m) deep, by an American team of experts were supposed to be conducted to establish the plane's identity. The lack of further information indicates that nothing came of this discovery.

Japanese capture research continues to focus on the time Amelia may have spent at Saipan. A group currently searching the island for evidence is Earhart on Saipan. This team's primary activities include interviewing witnesses with evidence related to the missing flyers and excavations at Aslito Airfield to locate remains of the Electra. Though frequently carried away with talk of conspiracies and government cover-ups, a good summary of evidence related to the Japanese prisoner theory is Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last.

A final project worth noting concerns the uncertainty regarding how far Earhart and Noonan could have traveled on their final flight. A group called The Electra Project has attempted a high-fidelity flight simulation of the Lockheed plane and may shed light on the matter. The group's findings suggest it was unlikely the aircraft had enough fuel to reach anywhere but Howland and could have well gone down east of the island where no sonar search has yet been conducted. Nevertheless, simulations are only as good as the models and assumptions that go into them, and many of the inputs required can never be conclusively known.

It is now 77 years since Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan vanished on their ill-fated flight. After so much time, it

is remarkable how many groups continue expeditions and research trying to solve the mystery.

- answer by Jeff Scott, 28 September 2014

Read More Articles:

|

Aircraft | Design | Ask Us | Shop | Search |

|

|

| About Us | Contact Us | Copyright © 1997- | |||

|

|

|||