|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

This depth of experience in building small solid rockets would soon be applied again to the lofty goal of launching America's first satellite into Earth orbit. While various scientific institutions had investigated this subject, launching a satellite was not considered a high priority by the US government. That policy quickly changed following the Soviet launch of Sputnik in October 1957. This demonstration of Soviet scientific progress and technological skill prompted the United States to launch a number of independent efforts under a variety of government agencies to match the feat.

Among the organizations tasked with meeting this challenge was the Naval Ordnance Test Station. Given the facility's expertise in developing air-launched weapons powered by small solid rockets, it is not surprising that the NOTS design built upon this experience. Though nicknamed NOTSNIK (or NOTSnik) for a combination of NOTS and Sputnik, the acronym was said to stand for Naval Ordnance Test Satellite and the program was officially known as Project Pilot. The vehicle was also referred to by the designation NOTS-EV-1.

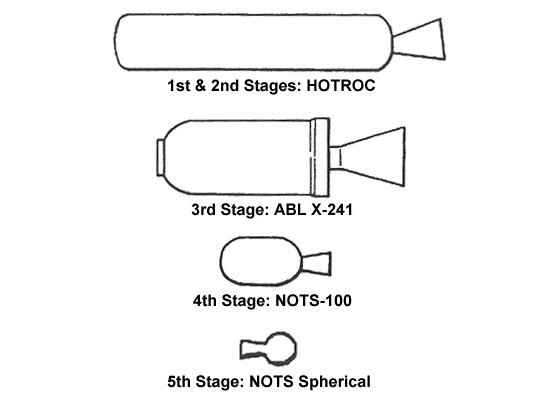

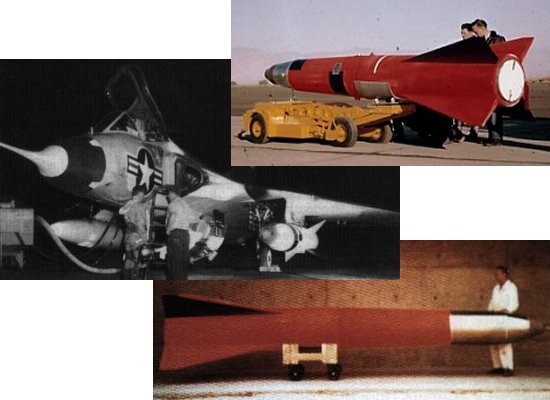

Approved in early 1958, the project proceeded rapidly by relying on existing rocket motors and other components readily available. The NOTSNIK vehicle was carried aboard a Douglas F4D-1 Skyray fighter to a high altitude where its rocket motors were fired for the trip into orbit. The rocket was designed to be released while the F4D-1 was traveling at a speed of more than 450 mph (725 km/h) and in a 50° climb to a launch altitude of 41,000 ft (12,500 m). Upon release, the first of five rocket stages was ignited. Both the first and second stages included two HOTROC solid rocket motors derived from the booster used on the SUBROC anti-submarine rocket-boosted torpedo. The first stage rockets ignited three seconds after release from the parent aircraft and remained operational for just five seconds. Following a twelve second coast phase, the second stage pair of HOTROC motors ignited for another five second burn.

By the time the second stage exhausted, NOTSNIK had achieved an altitude of about 50 miles (80 km). The structure containing both the first and second stages was then jettisoned as the third stage ignited. Consisting of an ABL X-241 solid rocket, this stage burned for 36 seconds before the fourth stage motor ignited for a 5.7 second long burn. By now, the vehicle had reached a very low and extremely eccentric transfer orbit. The orbit was stabilized into a more circular orbit by the fifth and final stage consisting of a NOTS 3-inch Spherical rocket motor.

This combination of rocket stages boosted by an aircraft launch platform had the capability to place a very small payload of just 2.3 lb (1.05 kg) into an orbit of 1,400 miles (2,250 km) altitude. The payload reportedly included a small infrared camera, designed to take images of the ground or collect weather data, and a transmitter to return signals to Earth. Since this payload could potentially be used as a reconnaissance system, the entire project was classified top secret and remained unknown to the public for many years.

The NOTSNIK concept was designed primarily for simplicity by using more reliable solid rockets compared to the complex liquid rockets carried by other launch vehicles. NOTSNIK also had no guidance system since such a device would have increased complexity and taken up vital space and weight. The vehicle instead relied on large tail fins to stabilize the craft along its trajectory, and there was no attempt made at achieving a specific orbital inclination. The lack of liquid rocket engines and a control system resulted in a launch vehicle with no moving parts.

Despite its intended simplicity, NOTSNIK suffered from difficulties integrating so many off-the-shelf components. The first flights attempted were two ground test launches to test the first and second stages. Occurring in July 1958, both of these tests failed when the vehicle exploded shortly after liftoff. Two more ground launches were attempted the following month but were also unsuccessful due to fin structural failures within four seconds of launch. Despite this inauspicious start, the first manned launch from the F4D-1 Skyray aircraft was attempted on 25 July. A second attempt came two weeks later and four more Skyray shots were launched in late August. The F4D-1 used during these tests took off from the NOTS field at Inyokern, California, and conducted the launches over the Pacific sea ranges off Naval Air Station Point Mugu.

Of the six orbital launch attempts, four malfunctioned almost immediately. In all four cases, either the NOTSNIK vehicle exploded shortly after ignition or the first stage failed to ignite and the rocket fell into the Pacific Ocean. Nevertheless, the fate of the first Skyray launch on 25 July and the third on 22 August was never conclusively determined. Both shots rapidly climbed out of view of the launch and chase aircraft and appeared to function properly. While either one might have reached orbit to become one of America's first satellites, radio communications were lost and the success of the satellite could not be confirmed. The only possible evidence of success came from a tracking station in Christchurch, New Zealand, that reported receiving a very weak radio signal during the 22 August launch at the times expected for the first and third orbits. However, these spurious signals most likely came from another source. Most of those involved in the project doubted that the NOTSNIK satellite actually achieved orbit.

This lack of apparent success led to the cancellation of further NOTSNIK launches, but the effort gained a second lease on life just a year or two later. Officially known as Project Caleb, though it may have unofficially been dubbed NOTSNIK II, this new effort was an improved version of the Project Pilot vehicle called NOTS-EV-2. This rocket was intended to provide a rapid-reaction capability to launch small payloads into orbit for reconnaissance missions. Similar to the original NOTSNIK, the Project Caleb vehicle was designed for launch from a manned aircraft and included four solid rocket stages. The troublesome HOTROC boosters that plagued NOTSNIK were done away with and NOTS-EV-2 instead employed a NOTS-500 first stage, ABL X-248 second stage, NOTS-100A third stage, and a spherical NOTS rocket motor fourth stage.

The first NOTS-EV-2 flight occurred on 28 July 1960 when the vehicle was launched from the same F4D-1 Skyray that had been used during the original NOTSNIK program. Though only a test flight with just a single rocket stage, the flight was a success. A second launch attempted in October tested a two-stage vehicle, but this flight failed when the second stage did not ignite. Despite promising potential, further development of an orbital version of the Caleb rocket was soon cancelled due to pressure from Air Force officials fearful of possibly losing satellite launches to the Navy.

Yet like a cat with nine lives, the project managed to find a new reason for being and continued as a sounding rocket under the name Hi-Hoe. Testing of this latest form commenced in October 1961 when the first of three launches of a two-staged suborbital rocket design was attempted. Having outgrown the Skyray, the Hi-Hoe vehicles were instead carried aboard the higher performance F-4 Phantom II fighter. The first two tests proved unsuccessful after suffering second-stage failures, but the third launch on 26 July 1962 managed to reach a peak altitude of 725 miles (1,165 km).

Still another variation of the NOTSNIK concept was developed during this period as an early anti-satellite (ASAT) weapon. Known as the Satellite Interceptor Program (SIP), two of the NOTS-EV-2 vehicles were adapted for ground-launch tests of a possible ASAT application. These tests were conducted in October 1961 and May 1962 at San Nicolas Island off the California coast and were apparently successful, though few details are known.

Although further development of the NOTSNIK series of rockets ended by the mid-1960s, interest in the concepts pioneered by these unique rockets has recently been rekindled. Perhaps the most ambitious project investigating NOTSNIK technology is a NASA mission to return samples of soil and rocks collected on Mars to researchers on Earth. This sample return mission, tentatively planned for the early 2010s, requires a relatively simple, reliable, and lightweight booster rocket that can be transported to the Martian surface. Once a separate rover mission had collected samples, they would be placed aboard the booster and lifted into orbit to rendezvous with a spacecraft. The payload would then be loaded aboard this vehicle for return to Earth.

The attractiveness of a NOTSNIK-type booster is the lack of moving parts, reliability and long-term storability of

solid rocket motors, and reduced need for heavy and complex control systems. Though improvements would have to be

made to many of the NOTSNIK systems to support the guidance needs of an orbital rendezvous, many of the propulsion

and stability systems developed during Projects Pilot and Caleb are well suited to a Mars Sample Return mission.

Should NASA mission planners choose to pursue this approach, perhaps we will see yet another incarnation of NOTSNIK

rise again, though not as a weapon of Cold War paranoia but as an instrument of scientific exploration.

- answer by Jeff Scott, 23 April 2006

Related Topics:

Read More Articles:

|

Aircraft | Design | Ask Us | Shop | Search |

|

|

| About Us | Contact Us | Copyright © 1997- | |||

|

|

|||