|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

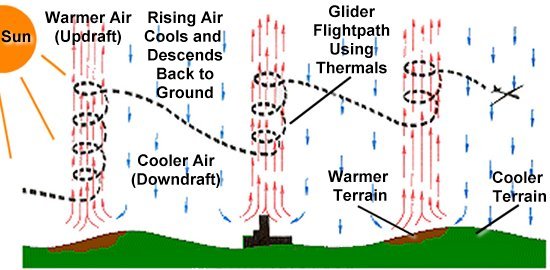

Thermals form as a result of uneven heating of the air near the ground that is often due to difference in terrain or the presence of buildings. Thermals are particularly common near hills, for example, since the Sun heats one side of the hill while the other is shadowed. As the sunny side of the terrain absorbs the Sun's heat, the air above it is warmed while the air above the shadowed terrain remains cooler. Buildings are also good at absorbing heat and can create similar effects. These differences in temperature create convective currents that cause the air to begin circulating.

Warmer air is lower in density and starts to rise, creating the updrafts that thermals are known for. Air is colder at higher altitudes, however, so this rising mass of air is gradually cooled until it can rise no further. This cooled air then descends back to the ground and falls towards the cooler terrain that has been shadowed from the warmth of sunlight. As additional air is pulled over the warmer terrain to be heated and rise, the process repeats and keeps the convective circulation going. This process is similar to the convective air currents that create and sustain a hurricane.

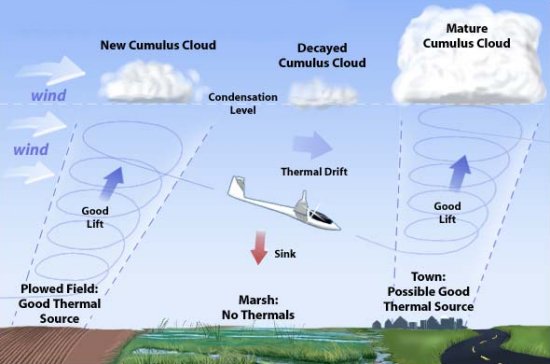

Thermals are most often found during the morning and early afternoon. These air currents begin to form in the early morning as the Sun rises and starts to heat the cool night air. The thermal air currents intensify as the Sun moves higher in the sky and the heating strengthens. As the Sun begins to descend during late afternoon and evening, the convective currents lose their strength and thermals break down.

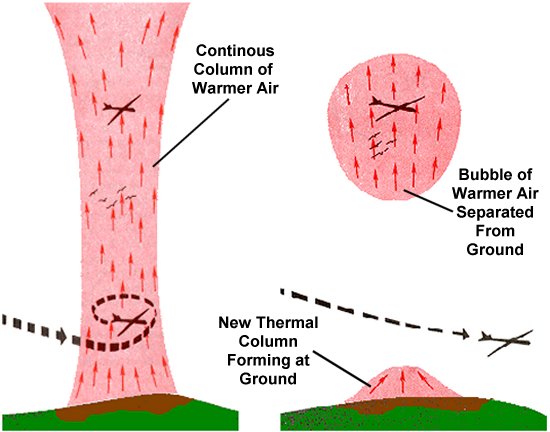

There are two main types of thermals that form in similar ways but vary in structure. The columnar type of thermal forms at the ground and consists of a continuous column of rising air that swirls upward into the sky. An observer on the ground may be able to spot this type of thermal if it pulls debris like dust or leaves upward, and it is often visible as a dust devil. Another common method to spot the location of a thermal plume is to observe clouds. The cooling air inside a rising thermal column sometimes causes water vapor within the air mass to condense into a cumulous cloud. A cumulous cloud that is still growing and in the process of forming is a good indication that a thermal is present.

A second type of thermal is referred to as a bubble or vortex-ring thermal. This variety of thermal also forms at the ground but eventually separates to form an independent, self-contained bubble of rising warm air. The bubble grows as it rises into the sky because of decreasing atmospheric pressure, and it will eventually break apart once the pressure differential becomes too great. This type of thermal is generally difficult to spot once it separates from the ground, but the formation of a new columnar thermal beneath it may be indicative that a ring-vortex is also present.

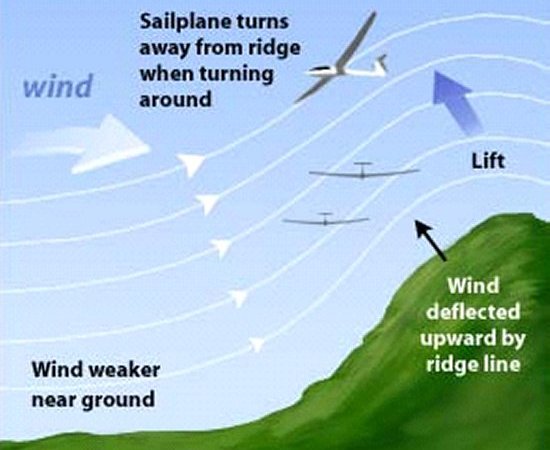

In addition to thermals, a related type of atmospheric phenomenon is called slope soaring or ridge soaring. As winds approach the side of an obstacle like a hill or large building, the air is deflected upward. A bird or glider flying within this deflected air flow will also be carried upward to a higher altitude with very little effort. These rising winds can be created by a variety of obstacles including hills and cliffs, groups of buildings, groves of trees, or a large ocean wave. If the wind is strong enough, the deflected air may rise tens or even hundreds of feet in altitude.

Birds like pelicans often take advantage of slope soaring by flying directly towards a cliff or building and allowing the deflected air flow to carry them over the top of the obstacle, rising to a higher altitude in the process. Otherwise, it is generally more common to see smaller, low-altitude birds engaging in slope soaring. While thermals often rise thousands of feet above the ground and are attractive to large soaring birds, slope soaring is generally limited to much lower altitudes where these large birds seldom fly.

Sailplane pilots and remote control glider flyers can also take advantage of slope soaring to remain airborne for extended lengths of time. These pilots usually do so by flying back and forth over the upwind side of the ridge, much like a surfer riding a wave. The pilot must be careful to pull out of the air flow at the correct time, however, or the downdraft on the other side of the object can pull the glider down in altitude as well.

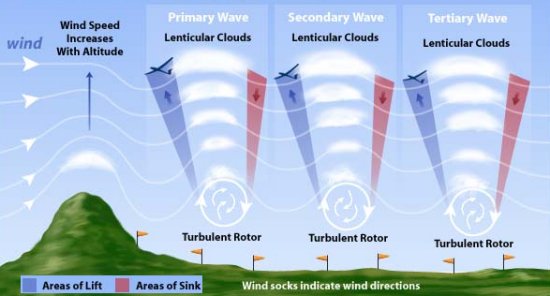

A similar type of soaring on a larger scale is referred to as mountain wave soaring. A mountain wave is a unique phenomenon that occurs when a strong wind blows perpendicular to mountains. This wind flows over the top of the mountain or ridge and down the opposite side before impacting the ground or a layer of air near the ground. This impact causes the air to deflect back upwards by thousands or tens of thousands of feet. The deflected air then impacts against another layer of air like the boundary between the troposphere and stratosphere that bounces the deflected air back towards the ground. This cycle of upward and downward motion creates a repeating wave that can occur several times downwind of the mountain.

The strong updrafts created by mountain waves can pull a bird or sailplane upward at very high rates, and peak altitudes of 35,000 ft (11,000 m) are not uncommon. Like thermals, a good indication of the presence of mountain waves can be seen in cloud formations. As the air blows over the mountain peak, water vapor within the air may condense to form a lenticular cloud. Additional lenticular clouds may also form downstream as each peak of the wave bounces off the high-altitude air layer.

Thermals are widely used by birds and humans alike because they make it possible to reach much higher altitudes

than could be reached otherwise. One of the best methods we have yet developed to identify thermals is simply to

watch the birds and observe when they begin flying in these spiraling, circular patterns. Indeed, it is also

interesting to note that birds often do likewise. It is not unusual for a pilot who has successfully discovered a

thermal to soon find him or herself sharing the rising air currents with a variety of birds that have come along to

enjoy the beneficial updrafts as well.

- answer by Jeff Scott, 4 December 2005

Related Topics:

Read More Articles:

|

Aircraft | Design | Ask Us | Shop | Search |

|

|

| About Us | Contact Us | Copyright © 1997- | |||

|

|

|||