|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

In the meantime, proponents of the ADF kept the concept alive by developing a new variant called the F-XX. This aircraft was designed for air superiority like the F-X, but intended to be much smaller, simpler, and less expensive than the F-15. Pentagon officials were so impressed by the idea that they recommended both the Air Force and Navy adopt the F-XX and cancel the F-15 and F-14 Tomcat that were rapidly escalating in price. Neither service chose to do so, however, since they believed the F-14 and F-15 were essential to future defense plans.

These ideas only began to change during the late 1960s. Increasing defense spending and growing budget deficits prompted the Nixon Administration and Congress to seek methods of reducing military procurement costs. This new political climate made a smaller, less expensive fighter an attractive option that could allow the production of more expensive projects like the F-15 to be scaled back. At the same time, Pentagon acquisition officials adopted a new philosophy of competition to encourage contractors to offer better products at lower cost. These two concepts culminated in the Light Weight Fighter (LWF) competition announced in 1971.

The purpose of the LWF was to complement the air-superiority mission of the F-15 with a smaller and less high-tech air defense fighter. The Light Weight Fighter Request for Proposal (RFP) emphasized high thrust-to-weight ratio, low weight, and low cost. Instead of the high-speed requirement adopted for the F-15, the LWF was to focus on good maneuverability at the transonic speeds where most air combat occurs. The LWF also emphasized small size since combat in Vietnam had shown that the small, agile MiG-17 and MiG-21 were much harder to spot visually than their larger American counterparts.

The RFP elicited proposals from five aircraft manufacturers including Boeing, General Dynamics, Lockheed, Northrop, and Vought. The Boeing Model 908, shown below, featured a single engine in a cylindrical fuselage fed by a large chin-mounted inlet. With its swept wings and conventional tail surfaces, the Boeing proposal looked very similar to the final winning F-16 design.

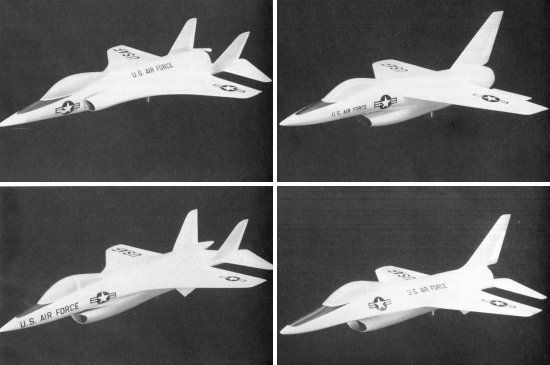

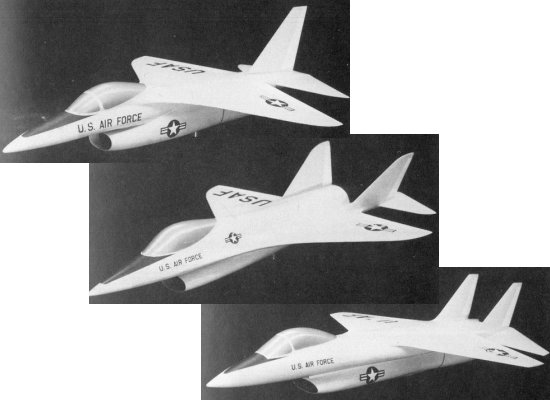

General Dynamics had been studying potential designs for a light fighter for several years, including those illustrated below. Most adopted a similar propulsion and inlet layout but explored different wing and tail configurations. A chin inlet below the forward fuselage was considered ideal due to its better performance at high angles of attack compared to inlets located on the side of the fuselage.

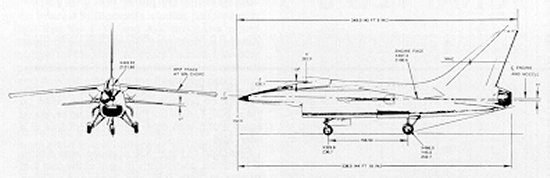

Other designs evaluated a single vertical tail versus a twin tail layout. A single tail was eventually adopted since wind tunnel tests had shown this configuration improved the performance of the wing leading edge root extensions. Still more studies were performed on various wing designs including straight, delta, swept, and variable geometry layouts. A variable geometry wing like that used on the F-111 and F-14 was rejected because of cost and complexity while the delta was also eliminated due to poor maneuverability. A relatively conventional straight wing with leading edge sweep was ultimately selected as the best compromise between maneuverability and low drag. The wing root was also blended into the fuselage to further enhance aerodynamics. These studies resulted in the definitive Model 401-16B submitted by General Dynamics as its LWF proposal.

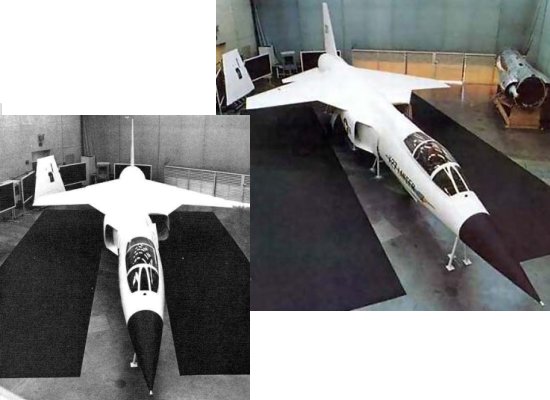

Lockheed's proposal was based on the company's earlier F-104 Starfighter that had become a successful light fighter throughout Europe. Lockheed had funded development of the CL-1200 Lancer as a competitor to the F-5E Tiger II for export sales. Compared to the F-104, the Lancer had a larger wing moved further aft and mounted higher on the fuselage.

Otherwise, the Lancer used the same fuselage and engine inlets as the original F-104. Unfortunately for Lockheed, the F-5E went on to capture the bulk of the foreign fighter market. The US Air Force, however, showed some interest in the concept and considered buying one as an experimental prototype under the designation X-27. This variant replaced the conical inlets of the F-104 with rectangular inlets like those on the mock-up shown below. Though the X-27 was cancelled for lack of funds, the concept was resurrected and submitted to meet the LWF requirement.

Northrop, unlike the other competitors, submitted a twin-engine design. Northrop had begun development of the Model P-530 as a high-performance fighter to eventually replace the F-5E in its product line. Though the P-530's wing was based on the F-5, it was enlarged, moved higher on the fuselage to create more room for weapon carriage, and combined with leading edge root extensions (LERXs) to improve performance at high angles of attack. Northrop also evaluated numerous inlet and vertical tail configurations, like General Dynamics, but came to opposite conclusions. Northrop preferred side-mounted inlets after finding that the LERX position helped to guide air into the inlets and maintain good flow even at extreme angles. In addition, a twin-tail layout was deemed advantageous since the tails would not be blocked by the fuselage at high angles of attack. This arrangement also allowed the tails to be canted to improve yaw effectiveness and reduce radar cross section.

The P-530 was unveiled in 1971 but failed to attract any customers. Undeterred, Northrop submitted the design to the LWF competition. The Northrop entry was renamed the P-600 since it had been slightly modified to meet the specific LWF requirements. The P-600 also incorporated a new simplified landing gear design to reduce weight, a fly-by-wire control system was added, and many structural components were redesigned to make use of graphite fiber composite materials.

Vought responded to the RFP with a derivative of the successful F-8 Crusader / A-7 Corsair II family known as the V-1100. The V-1100 featured an enlarged fuselage for a more powerful engine and a modified wing to improve maneuverability. The forward fuselage was also redesigned to improve pilot visibility compared to the F-8 and A-7.

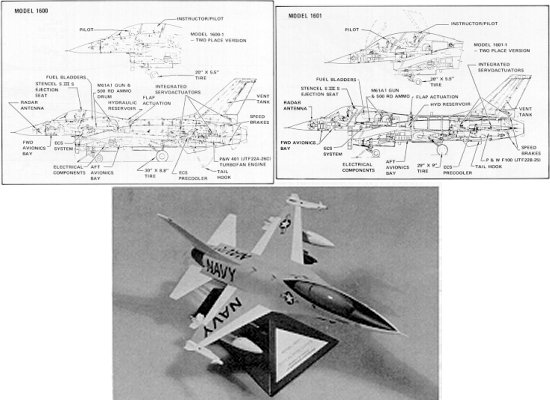

Vought also teamed with General Dynamics to develop a derivative of the LWF concept for the Navy, much like Northrop and McDonnell Douglas did for the P-600. The resulting Vought Models V-1600 and 1601 were based on the General Dynamics Model 401 but incorporated features from Vought's many successful naval aircraft.

Upon reviewing these five proposals, the Air Force initially judged the Boeing 908 as the best with the General Dynamics 401 and Northrop P-600 as close seconds. The Lockheed CL-200 Lancer and Vought V-1100 were both deemed unacceptable and eliminated. After further examination, the General Dynamics and Northrop designs were judged superior and the Boeing concept was also eliminated. General Dynamics and Northrop were subsequently awarded contracts to build two prototypes each. These prototypes were evaluated as the YF-16 and YF-17.

The two sets of prototypes participated in a competitive "fly-off" from 1972 to 1974. Though both designs had

their advantages, the YF-16 was ultimately named the winner of a production contract in 1975. By this time, the

LWF had been renamed the Air Combat Fighter (ACF) to attract additional foreign customers. Not all was lost for

Northrop, however, since the losing YF-17 had won praise from the Navy and later evolved

into the F-18 Hornet. The former rivals have since become two of the

most successful jet fighters ever built by the United States. Over 4,000 examples of the F-16 have been built for

service with at least 24 different countries. The F-18 has also been sold to eight nations with over 1,600

aircraft built to date, including the latest F-18E/F Super Hornet.

- answer by Molly Swanson

- answer by Jeff Scott, 10 July 2005

Read More Articles:

|

Aircraft | Design | Ask Us | Shop | Search |

|

|

| About Us | Contact Us | Copyright © 1997- | |||

|

|

|||