|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

Though the Concorde has been retired for the past year, the supersonic transport remains a frequent source of questions. This week's article answers several of the questions we have received and is a continuation of those covered in Part I.

These temperatures rose even higher at the Concorde's maximum rated speed of Mach 2.2, with a peak nose temperature of 153°C (307°F). If those temperatures aren't impressive enough on their own, just consider that the outside air temperature at the Concorde's cruise altitude of 17,000 m (56,000 ft) is only -57°C (-70°F)!

This external heating had a significant impact on the construction of Concorde. Perhaps the most important issue designers had to contend with was the fact that heat causes materials to expand. I've seen different values on exactly how much the aircraft expanded, but most sources indicate that the airframe stretched by 5 to 12 inches (12 to 30 centimeters) at Mach 2. Given the aircraft's normal length of 204 ft (62.2 m), that change amounts to less than a 5% increase in the size of the Concorde fuselage.

That is not to say that the issue was not a problem. Far from it! The most significant challenge the manufacturers had to address was to select a material that could withstand the heat and expansion while maintaining its mechanical properties throughout the life of the aircraft. Most conventional airliners are built out of aluminum because of its high strength and relatively low weight. Unfortunately, traditional aluminum alloys cannot survive the high temperatures experienced by Concorde. More exotic materials like titanium could have been used, but these are very expensive and often too heavy for use on such a large plane.

The manufacturers instead chose a new advanced alloy of aluminum developed by Rolls-Royce to survive high temperatures. This alloy was known as CM001, CM002, or CM003 depending on the recipe used for the various components. While this aluminum alloy lowered costs and saved weight, it was still inadequate for some areas of severe heating where steel or titanium had to be used.

A further problem designers had to address was the uneven changes in temperature across the aircraft during different phases of flight. This problem was most significant during acceleration to Mach 2 to reach cruise conditions and deceleration prior to landing. These uneven changes in temperature caused some parts of the plane to expand or contract more rapidly than others. This problem resulted in greater stresses and loads acting on the plane's structure at different phases of the flight. Designers were able to overcome these effects by allowing various parts of the plane to move with respect to one another, thereby easing the internal stresses. Examples of these sliding connections included corrugated spar webs, diamond-shaped cutouts, and slotted lug attachments.

While it may seem low-tech, the Concorde's external paint was also chosen to help alleviate the problems of

thermal expansion. The white paint was specially developed to help dissipate the heat generated on the surface of

the plane at high speed. The paint was also designed to be flexible so that it would not flake off the plane

during the thermal expansion and contraction experienced in flight.

- answer by Joe Yoon, 24 October 2004

The following table lists the final location of each Concorde with links to museums or other sites where they are displayed.

| Popular Name | Registry | Operator | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

|

001 (prototype) |

F-WTSS | Sud-Aviation |

Musée de l'Air et de l'Espace Le Bourget, France |

|

002 (prototype) |

G-BSST | BAC |

Fleet Air Arm Museum Royal Naval Air Station Yeovilton Somerset, UK |

|

01 / 101 (pre-production) |

G-AXDN | BAC / Aérospatiale |

Imperial War Museum Duxford, Cambridgeshire, UK |

|

02 / 102 (pre-production) |

F-WTSA | Aérospatiale / BAC |

Musee Delta Paris Orly Airport Orly, France |

|

201 (test) |

F-WTSB | Aérospatiale / BAC |

Airbus factory Toulouse, France |

|

202 (test) |

G-BBDG | BAC / Aérospatiale |

Brooklands Museum Weybridge, Surrey, UK |

|

203 (production) |

F-BTSC (F-WTSC) |

Air France |

Crashed in 2000 Wreckage stored at Le Bourget, France |

|

204 (production) |

G-BOAC | British Airways |

Manchester Airport Aviation Viewing Park Manchester, UK |

|

205 (production) |

F-BVFA | Air France |

Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center Washington Dulles Airport Chantilly, VA, USA |

|

206 (production) |

G-BOAA | British Airways |

National Museums of Scotland Museum of Flight East Fortune Airfield near Edinburgh, Scotland |

|

207 (production) |

F-BVFB | Air France |

Auto & Technik Museum Sinsheim, Germany |

|

208 (production) |

G-BOAB | British Airways |

BAA Heathrow Airport London, UK |

|

209 (production) |

F-BVFC | Air France |

Airbus factory Toulouse, France |

|

210 (production) |

G-BOAD | British Airways |

Intrepid Air and Space Museum New York, NY, USA |

|

211 (production) |

F-BVFD | Air France |

Retired in 1982, scrapped in 1994 Remnants stored at Le Bourget, France |

|

212 (production) |

G-BOAE | British Airways |

Grantley Adams International Airport Bridgetown, Barbados |

|

213 (production) |

F-BTSD (F-WJAM) |

Air France |

Musée de l'Air et de l'Espace Le Bourget, France |

|

214 (production) |

G-BOAG (G-BFKW) |

British Airways |

Museum of Flight Seattle, WA, USA |

|

215 (production) |

F-BVFF (F-WJAN) |

Air France |

Charles de Gaulle Airport Paris, France |

|

216 (production) |

G-BOAF (G-BFKX) |

British Airways |

Bristol Aero Collection Filton, Bristol, UK |

Note that some of these aircraft are currently in storage pending delivery to the museums where they will

ultimately be displayed. More information can be found at the links provided.

- answer by Molly Swanson, 24 October 2004

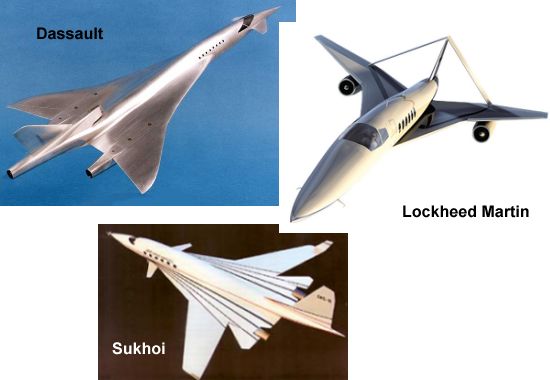

The most likely prospect for a new supersonic passenger plane is not a commercial airliner but a business jet aimed at a very small segment of the flying public. The Concorde's only commercial success came as the result of catering to the wealthy elite who needed to make rapid long-distance trips, so this market is likely to be most receptive to a supersonic replacement. Many aircraft manufacturers believe that a Supersonic Business Jet (SSBJ) could generate strong sales to corporations, private owners, and executive jet services.

The class of supersonic passenger aircraft that is most likely to take the place of Concorde in the short term is small business jets seating about 5 to 20 passengers. It is more economical at this time to cater to a small group of business executives and celebrities than to build a plane capable of carrying 100 or more airline passengers. Airlines are not interested in supersonic aircraft because of their high operating costs, but high-speed travel does appeal to "the rich and famous" or powerful executives who are not nearly as concerned about the bottom line. Business and executive jets are aimed primarily at this clientele to begin with, so that appears to be the most likely market for supersonic travel. A number of aircraft manufacturers have already unveiled SSBJ proposals, including Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, Dassault, Gulfstream, and Sukhoi. A new startup company named Aerion Corp. has announced plans to build a 12-passenger SSBJ by 2011.

Since most nations still prohibit supersonic travel over their territories, particularly over populated areas,

these supersonic business jets would most likely operate over the ocean. They would probably be based at large

coastal cities and fly between major trans-oceanic centers of business, like New York and London or Los Angeles and

Tokyo.

- answer by Jeff Scott, 24 October 2004

Related Topics:

Read More Articles:

|

Aircraft | Design | Ask Us | Shop | Search |

|

|

| About Us | Contact Us | Copyright © 1997- | |||

|

|

|||