|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

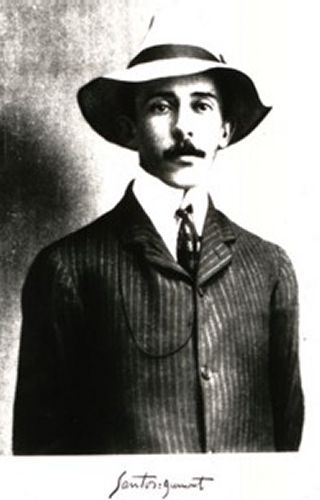

Alberto Santos-Dumont was born in Brazil in 1873, the youngest off 11 children. His father owned a large coffee plantation that was so successful he became known as the "Coffee King of Brazil." Much of the elder Santos-Dumont's success was due to his skill in engineering and his ability to create labor-saving machines to improve production and reduce expenses. This fondness for machinery rubbed off on Alberto at a young age, and he later wrote that his dreams of flying vehicles began while he was still a boy. At the age of 17, Alberto and his parents moved to Paris after selling the plantation following a tragic accident that left his father paralyzed.

Few places could have been better for the young Alberto since France was generally regarded as the world leader in aviation research during the late 1800s. Santos-Dumont was first attracted to balloons and other lighter-than-air vehicles. He soon began building balloons and successfully piloted a design of his own, the Brésil, in 1898. Shortly thereafter, Santos-Dumont began experimenting with a more advanced class of vehicle called dirigibles that carried engines to provide propulsion. By 1905, Alberto had succeeded in building and flying no fewer than eleven dirigibles of his own design.

His greatest interest came in finding the ideal means of steering of such craft. Santos-Dumont was so successful in this endeavor that his dirigible Number 3 was able to takeoff, circle the Eiffel Tower a few times, and land flawlessly in 1890. Santos-Dumont's greatest achievement came in 1901 when he piloted his dirigible Number 6 from Parc Saint Cloud to the Eiffel Tower and returned in less than thirty minutes. The feat earned Santos-Dumont the Deutsch Prize of 100,000 francs and made him a world-wide celebrity. His continued success in the field brought such fame and fortune that Santos-Dumont was invited to the White House to meet President Theodore Roosevelt in 1904.

After making so many strides in balloons and dirigibles, Santos-Dumont's trip to America exposed him to the work of the Wrights and inspired him to turn his attention to heavier-than-air flight. His most significant accomplishment in this field was his first plane called the 14-bis completed in 1906. Like the Wright Flyer, Santos-Dumont's design was a biplane using a canard surface for stability. However, the 14-bis differed notably by using a structure reminiscent of a box kite for the lifting surfaces. Furthermore, the cockpit was unusual in that the pilot stood upright in a wicker basket located between the wings near the back of the aircraft.

Santos-Dumont initially powered his craft using a 24-hp engine turning a single aft-mounted pusher propeller behind the cockpit. Prior to making a proper flight in his design, Alberto performed some innovative testing by applying his skill in dirigibles. In July 1906, Santos-Dumont conducted "test flights" by suspending the boxy 14-bis beneath his dirigible Number 14.

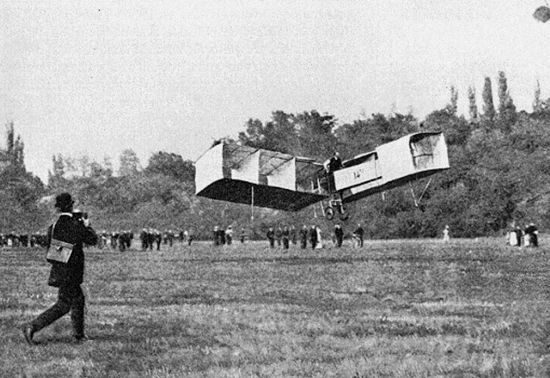

Alberto is said to have taken the 14-bis on a short hop of 23 ft (7 m) on 13 September 1906, but the plane was damaged on landing. While making repairs, Santos-Dumont also concluded that the aircraft was underpowered and retrofitted a more powerful 50-hp engine. Thanks to this improvement, Santos-Dumont successfully flew nearly 200 ft (60 m) at an altitude of 10 ft (3 m) before a large crowd on 23 October 1906. Among the witnesses were members of the Aero-Club De Frances who certified the feat as the first verifiable flight of a powered airplane in Europe. Santos-Dumont was also awarded the Archdeacon Prize for his flight.

Spurred on by his success, Santos-Dumont made further improvements to his plane by adding ailerons and other refinements. In this form, the 14-bis succeeded in traveling over 725 ft (220 m) to win a 1500 franc prize from the Aero-Club for the first 100-meter flight. Santos-Dumont continued his interest in aviation throughout the first decade of the 1900s. The last plane he built, La Demoiselle of 1908, is a landmark achievement in its own right since many consider it to be the genesis of the modern-day ultralight.

Though Santos-Dumont remained interested in aviation, he was forced to give up on further experimentation after being stricken by multiple sclerosis in 1910. He moved back to Brazil late in life, but passed away in 1932. It is believed that he committed suicide due to a deepening depression over his illness and his disillusion over the use of aircraft in warfare.

Returning to your question, the debate over whether the Wrights or Santos-Dumont flew first is primarily one of semantics. Santos-Dumont supporters claim that even though the Wrights may have flown in 1903, theirs was not a true flight since their plane required a catapult and a steady breeze to become airborne. In comparison, the 14-bis used conventional landing gear and was able to take off from an open field in calm air.

While these claims do have some merit to them, what is often overlooked is the fact that many key details of the Wright Flyer had become public in Europe in 1904 once the Wrights had received their patent. It is generally believed that Santos-Dumont made extensive use of this information in the design of his plane and that he would not have been successful without the Wright's influence. Furthermore, even if the Wright's first flight is discounted, detractors often overlook that the pair made three more flights that same day, the longest covering 852 ft (260 m) and lasting nearly one minute. Even more impressive are the accomplishments of the Wright Flyer II in 1904. Among these was the world's first circular flight and a five minute trip covering nearly three miles (4.8 km) that occurred on 20 September 1904, two years before Santos-Dumont's first flight.

Santos-Dumont supporters go on to argue that his flight was verified by the Aero-Club De Frances, the predecessor

of today's Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) that is considered an objective international body for

conferring aviation records. The only witnesses to the Wright brothers flights, however, were typically close

friends and family. On the other hand, it should be noted that the Aero-Club was a much different group in 1906

than it is today. Not only was the Club in a feud with the Wrights because of the brother's perceived

secretiveness and lack of cooperation, but several of its members were directly involved in and providing funding

for the work of Santos-Dumont. Given this inherent conflict of interest, the partiality of the Aero-Club is still

debated to this day. Regardless, no one can deny that Alberto Santos-Dumont made major steps in advancing the

design of the aircraft, and his achievements are still highly regarded by aviation historians.

- answer by Joe Yoon, 15 August 2004

Related Topics:

What are the most significant events in the history of aviation and space flight?

Read More Articles:

|

Aircraft | Design | Ask Us | Shop | Search |

|

|

| About Us | Contact Us | Copyright © 1997- | |||

|

|

|||