|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

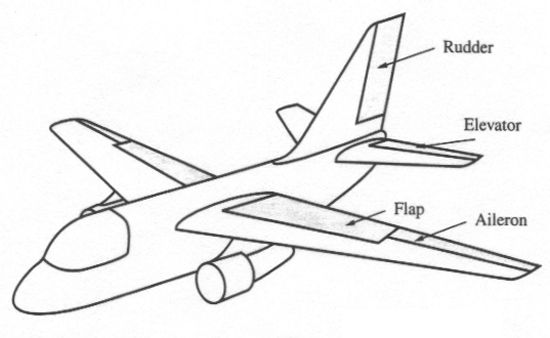

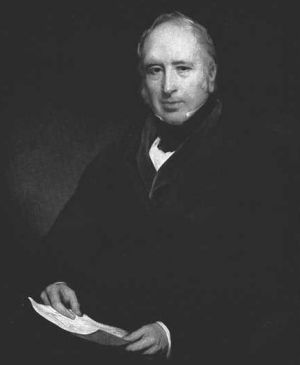

Much of the effort to develop these control surfaces was done during the 1800s when aviation pioneers like Sir George Cayley of Britain and Alphonse Penaud of France began experimenting with models and even manned gliders. They soon realized that aircraft would require some means by which to pitch the nose up and down and yaw the nose right and left. These ideas quickly evolved into the elevator and rudder, devices which were largely understood long before the Wright brothers flew in 1903.

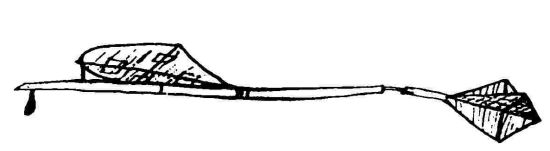

Cayley, in particular, spent much of the first half of the 19th century developing the basic design concepts that can still be seen in aircraft today. His 1804 glider, sketched below, incorporated a vertical and horizontal tail unit attached to a movable universal joint. The entire tail assembly was capable of rotating up and down such that it acted as an elevator.

This idea of deflecting the entire horizontal tail to act as an elevator persisted for over a century. The subsequent aeronautical developments of Otto Lilienthal in Germany, John Stringfellow in Britain, and Samuel Langley and the Wrights in America all continued to employ this technique. The rudder, which was likely inspired by ships and boats, was also utilized by most of the early pioneers. As with the all-moving horizontal tail, the Wrights and others usually employed all-moving vertical tails to act as rudders.

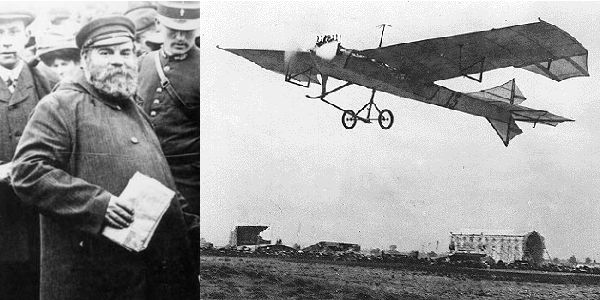

It was not until after the advent of powered, manned aircraft that these ideas began to change. The modern aircraft tail configuration was not seen until 1908 when Frenchman Léon Levavasseur constructed his Antoinette IV monoplane. This aircraft featured fixed vertical and horizontal tails with movable rudder and elevator surfaces attached to their trailing edges.

While the origins of the rudder and elevator are relatively clear, those of the aileron are argued to this day. Most aviation pioneers understood the need for the elevator and rudder to turn the aircraft in different directions, but few could foresee the importance of the aileron. These differing philosophies can be visualized best by comparing a demonstration flight of the Voison-Farman I biplane near Paris in January 1908 with that of the Wright A biplane near Le Mans in August of that year. Pilot Henri Farman's aircraft utilized only a rudder to turn and struggled to make a single turn in a sluggish, difficult manner. Meanwhile, Wilbur Wright stunned the French crowds with his graceful turns made possible by coordinating the rudder deflection with a development called wing warping.

The simple explanation of wing warping is that the two wingtips are twisted in opposite directions to increase the lift on one wing and decrease that on the other. The example shown above illustrates one of the Wrights' planes as viewed from the front. In this example, the trailing edge of the right wing is twisted downward from the original position indicated by the dashed lines. Meanwhile, the trailing edge of the left wingtip is twisted upward. The effect of this twisting action is that the angle of attack seen by the right wingtip is increased when compared to its initial position, and the left wingtip experiences a lower angle of attack. As angle of attack increases, lift also increases, so the right wing creates more lift than the left wing. This difference in lift causes the aircraft to roll right wing up (left wing down).

The Wrights had experimented with this idea in their early gliders. They had found that combining a rudder deflection with wing warping enabled complete control over the maneuvering of their aircraft and allowed effortless turns, banks, and figure-eights. By contrast, the European planes of the day, utilizing only a rudder, could only make turns while remaining essentially level to the ground, and their designs were far more difficult to maneuver.

But did the Wrights invent the aileron? Perhaps, but perhaps not. The first recognized aileron, a French word meaning "little wing," dates back to 1868 when an inventor named M. P. W. Boulton of England patented a concept for the use of such a device for lateral control. However, the idea was quickly forgotten since practical aircraft were still several years away. Other Europeans also proposed various ideas similar to wing warping or spoilers, but both were viewed more like speed brakes that would slow down one side of a plane and cause the aircraft to pivot about its vertical axis. The first to truly appreciate the function of such devices to perform banking flight was indeed the Wrights. So even though they may have not invented the aileron itself, they probably did "invent" the idea of using a control surface to provide roll control, an idea that no other major aircraft designer seems to have considered.

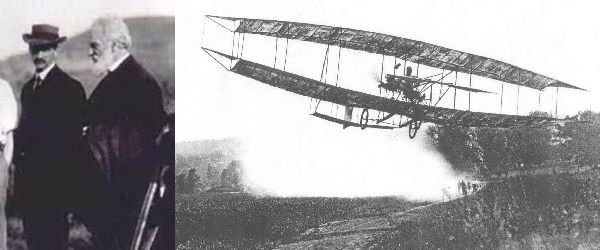

However, Wilbur Wright made over 100 demonstration flights throughout France in 1908 and gave the Europeans new impetus to improve the awkward, sluggish controls of their aircraft. Starting with the wing warping concept, designs soon evolved to include separate movable surfaces that resembled miniature wings. These "little wings" were sometimes referred to as "winglets," not to be confused with modern winglets which are vertical extensions of the wingtip. They were often mounted above or below the wing, in front of the wing, or sometimes placed in between the wings of a biplane.

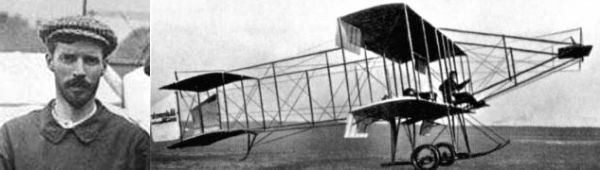

The first recognizable example of the modern aileron was not long in coming, however, and it was designed by no less than the aforementioned Henri Farman. His biplane, the Farman III, was equipped with four flap-like ailerons fitted at the outboard trailing edges of both the upper and lower wings. Farman's primary innovation was that he was the first to make ailerons an integral part of the wing, in the same manner we still use today, instead of the separate movable surfaces that had been used previously. These ailerons can be seen deflected downward in the picture below.

Farman's innovation was considerably more effective and less complicated than wing warping and was quickly adopted by virtually all the aircraft builders of the time. Only Orville Wright held out, but even his stubbornness gave way in 1915 when he finally converted to the aileron.

Yet the story still isn't over! A group of American aviation enthusiasts had formed the Aerial Experiment Association to build and fly new aircraft designs. They had realized the need for roll control, but were keenly aware that the Wrights had patented wing warping. Looking for an alternative, Alexander Graham Bell conceived of a device similar to the French aileron. A patent on the AEA's aircraft developments, including Bell's ailerons, was granted in 1911. Following the dissolution of the AEA, one of its leading members Glenn Curtiss continued to use the aileron on his new designs, which greatly angered the Wrights. Though the Wrights had patented wing warping, the patent was vague enough that it could be construed to cover any form of lateral control.

In response, the Wrights sued Curtiss for patent infringement and eventually won the case. Europeans like Henri Farman became quite alarmed by this development and were concerned that they too would be forced to pay the Wrights royalties for the use of ailerons. When French aviator Louis Paulhan came to the US to demonstrate his designs, three of his aircraft were impounded on the grounds of patent infringement.

Glenn Curtiss attempted to challenge the ruling, but the Wright claim was upheld in 1913. Orville began demanding a 20% royalty for any airplane with any form of lateral control built by any manufacturer, retroactive to the first plane produced. Luckily for the continued development of the aviation industry, World War I intervened. At the direction of the US Government, the patent litigation and royalties were set aside to focus on wartime production. While the patent battle could have been renewed at the conclusion of the war, neither side chose to do so, and the controversy finally died down.

So we are left with the original question--who did invent the aileron? The simple fact is that no one really knows

for certain. Strong claims could be made for Boulton, the Wright brothers, Farman, Bell, and Curtiss. The Wrights

certainly deserve the most credit for first recognizing the problem of roll control and devising a solution to it,

but Farman probably has the best claim for having invented the modern aileron that we still use today.

- answer by Joe Yoon, 17 November 2002

Related Topics:

Read More Articles:

|

Aircraft | Design | Ask Us | Shop | Search |

|

|

| About Us | Contact Us | Copyright © 1997- | |||

|

|

|||